How do gay writers celebrate the end of a book, a poem, a story? I don’t know about Sarah Orne Jewett, Langston Hughes, Willa Cather or Allen Ginsberg, but after that brief moment of relief, before the serious editorial worrying begins, after my sweetheart takes me for a long walk on the beach and a romantic dinner with a view, I clean my desk.

OK, I don’t clean it that night. Or the next day. It might take a month. Or two. I like to get a few short stories written between books, so the purging comes in fits and starts. But definitely before I begin the next book.

This time, after four years of concentrated writing and nine years of research on my new book, Rainbow Gap (due out in December), I’m still struggling with the logistics of making the desk optimally functional. For inspiration, I went on line.

I found a photo of Emily Dickinson’s desk. In an old issue of Amherst Magazine, Dickinson’s niece is quoted: Emily’s “only writing desk… a table, 18-inches square, with a drawer deep enough to take in her ink bottle, paper and pen. It was placed in the corner by the window facing west.” Eighteen inches square? No wonder she wrote such short poems. Didn’t she need space for her drafts? Her little red toy tractor? An index card file? Her thermometer/barometer? Oh—I guess that would be me.

I do the household filing and a while back that situation got out of hand. Our filing consists of shoving the right piece of paper into the right folder—eventually. I never expected the pile would climb to such heights. As a stopgap measure I plopped a cardboard inbox on the desk.

There were complications.

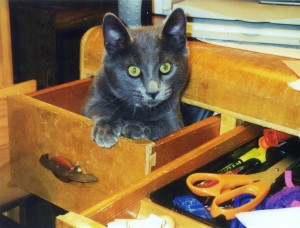

Our cat’s personal physician suggested some time ago that we provide stimulation with kibble “hunts.” It soon emerged that Bolo’s most stimulating place to hunt was my desk. Kibble could be found inside the overflowing inbox, under the escaped bills, behind the paperweights and hand thrown pots of pens, and inside irresistibly tiny boxes and mini-crates filled with small hand tools, pretty rocks, batteries, a penknife, outdated newspaper clippings—the ephemera of the writers’ trade.

The kitty dumped the contents of the inbox between the desk and the adjacent four-drawer file cabinet so often I placed a wicker trash can there and labeled it Inbox.

“There was a secret compartment in Henry James’ desk,” according to the brilliant biographer Leon Edel. He wrote that, when explored, no secret stash was discovered. I would have found something to put in that compartment, you betcha.

Louisa May Alcott’s “… father built her a half-moon desk between two windows and a bookcase to hold her favorite books.” That sounds a bit roomier than Emily’s. I wouldn’t want a desktop computer on it, though, cutting out the window view. I’ve learned to place my desk to one side of the window, so I can watch birds at feeders we’ve hung right outside. As a matter of fact, I just spotted my first Chestnut-backed Chickadee of the season. I’ll bet Louisa May was as distracted by the view as I am.

Langston Hughes was more disciplined. His very small manual typewriter and metal gooseneck lamp were on a desk that faced a wall. To use a typewriter, a sturdy desk was necessary. Hughes’ desk also held a large telephone, his cigarettes and matches. Neat, and a far cry from Emily Dickinson’s writing table.

Although Willa Cather is sometimes pictured with a substantial desk—perhaps after she moved to Greenwich Village—one of her writing desks was a “secretary.” I have my Nana’s secretary. Spindly legs, a flip down writing surface that rests on the open drawer for support. Some cubbies inside. A narrow shelf low to the floor. I never penned a word there.

Sarah Orne Jewett wrote at an elaborate secretary, more of a hutch with glass display case above, ample drawers below, and a hinged writing flap. I could no more write on a secretary than I could build a skyscraper on a placemat. Nana’s is in our kitchen storing address books and gewgaws.

A 1986 photograph Dave Breithaupt took of Allen Ginsberg’s desk, in his bedroom on East 12th in New York, shows neatly arranged stacks of paper, a lamp with a bare bulb, a pen. It looks as if Ginsberg tamed his desktop and would have known where to find exactly which page of “Howl” he was looking for. Of course, he had at least four, maybe six, drawers that hid who knows what.

James Baldwin’s desk was gloriously outrageous. Large, a photograph shows it covered edge to edge with paper and more paper and a great big electronic typewriter. My desk except for the machine.

Because writers no longer need desks. A desk makes a great surface for stapling and organizing. Its drawers are indispensable. I write seated in a small recliner, but it seems an apt celebratory ritual and homage to the queer writers before me to give my desk periodic respectful attention.

Lee Lynch wrote the classic novels The Swashbuckler and Toothpick House. Her newest book is An American Queer: The Amazon Trail, which is a Lammy finalist. Most recently she was made namesake and first recipient of the Golden Crown Literary Society Lee Lynch Classic Award for her novel The Swashbuckler. She is also a recipient of the James Duggins Mid-Career Award in Writing, and many more honors.Books by Lee Lynch are available at women’s and gay bookstores and at boldstrokesbooks.com