Directors Fenton Bailey and Randy Barbato on their definitive documentary of the artist

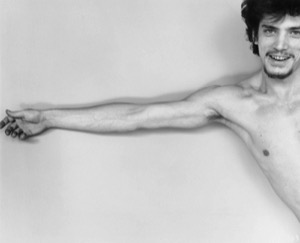

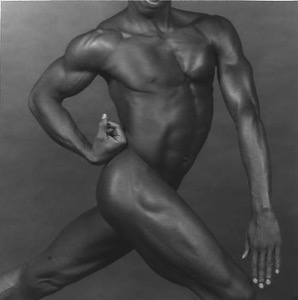

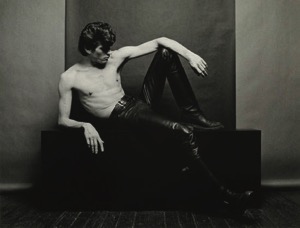

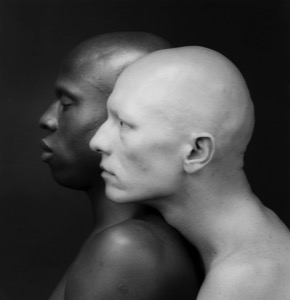

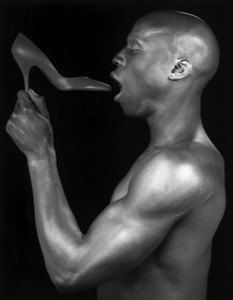

Last month, both the J. Paul Getty Museum and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art mounted their respective installations on famed photographer Robert Mapplethorpe. Titled Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Medium, both retrospectives attempt to narrate the complex arc of an artist who saw “perfection in form” in everything from flower petals to nudes while placing him in the canon of some of the finest photographers and artists of the second half of the 20th century, if not one of its most controversial.

To coincide with this much-needed visual history, directors Fenton Bailey and Randy Barbato (Inside Deep Throat, HBO’s Wishful Drinking and The Eyes of Tammy Faye) have released what they hope will be the definitive documentary of the artist, Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures.

The title stems from then-Sen. Jesse Helms’ (R-NC) comment expressing outrage over the National Endowment for The Arts’ (NEA) decision to fund an installation of Mapplethorpe’s – his last – at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C. (The Corcoran Gallery caved to the pressure but the installation became a center of controversy once again when the Contemporary Arts Center (CAC) in Cincinnati mounted the presciently-named The Perfect Storm. It resulted in obscenity charges against the museum and its director at the time Dennis Barrie. The charges were eventually dropped.)

San Diego LGBT Weekly had the chance to speak with the directors to help lend some perspective on someone who, although somewhat tamed by time, still provokes such aesthetical and illuminating reactions in an age of sexting, porn and reality television.

San Diego LGBT Weekly: I’ll start with the obvious: Why him? Why now?

Randy Barbato: It’s a really good question. The timing is perfect because, although Helms is long gone, his old state of North Carolina has just enacted a heinous and ridiculous anti-LGBT law. And we have Cruz, Trump and countless other racists, bigots and hypocrites seeking to close the American mind. Mapplethorpe said the purpose of art was to open something up – our hearts and our minds – and that is exactly what his work does. So why now? Because we need him more than ever!

Fenton Bailey: Like it or loathe it, Mapplethorpe’s art was about truth and honesty. Interestingly the Catholic League just attacked the film saying that we left out Mapplethorpe’s vicious attack on Cardinal O’Connor – the church’s equivalent of Nancy Reagan (i.e. not someone known for compassion for gay people). Anyway they said Mapplethorpe called him a “fat cannibal from the house of walking swastikas”. Of course Mapplethorpe never said any such thing. A simple google search reveals it was David Wojnaworicz. The point is that Mapplethorpe, in contrast to all this lying, was nothing but honest and direct.

What made Mapplethorpe the artist he was to become?

RB: As our film relates, he was gay and a misfit and something of an outcast within his own family. And like so many gay kids he had to go find his tribe which he did by moving to New York City. It’s a textbook rite of passage.

One critic of your documentary went on to write: “Having had a religious upbringing in Floral Park, N.Y., the photographer took many years to fully embrace his homosexuality, and with it, the gay leather aesthetic that would make him famous. Unfortunately, Look at the Pictures fails to understand how this conflict – and Mapplethorpe’s intense ambition to resolve this conflict through his photos – enhanced the artist’s work.” How do you respond to that criticism? Is it fair?

FB: It’s just not true and nothing in his work or his words supports that idea. Mapplethorpe was always gay and always OK with being gay. If it was a problem, it was other people’s problem. He was not conflicted. He was not tortured on the rack of Catholic guilt, like so many others. His work was all about showing what was in his life, documenting what he was into. There wasn’t a struggle.

His journey of self-discovery was not a tortuous path twisted by self-doubt. And even if he took pictures of torture, he was not himself tortured. He always knew who he was and completely confident and steadfast in his work. His fascination with all kinds of duality should not be mistaken for doubt, vacillation or some sort of struggle to choose.

RB: Yes, his first love affair was with a woman (as he himself admits in the film) but at his core he was always who he was. Our choice was to trust the artist by looking at the pictures and listening to his words, so none of this is really a matter of our opinion. Sure, people have theories that they can spin, but we suspect Mapplethorpe would have little time for them. He often didn’t read what was written about him. All that mattered to him was that he was written about.

Who influenced Mapplethorpe? Did he have any sort of protégés? Mentors?

RB: [Marcus] Leatherdale was a protégé and [Sam] Wagstaff was a mentor. But in both cases the relationship was much more complex than the usual mentor/protégé role might suggest. That’s why we see his evolution as an artist more in terms of a series of intimate collaborations in which each party brought something different to the table that would benefit the relationship. Everyone interviewed in the film knew Robert intimately and none of them characterized the relationship as exploitational. There was always some reciprocity.

The New York Times writes: “When [Mapplethorpe] was an art student, photography was considered as much craft as art. As a photography critic and a former picture editor at The New York Times says in the film, the genre would gain stature concurrently with the gay rights movement. Do you believe that to be true? Why?

RB: Yes, it is true. Were they merely parallel developments or was there a connection, some kind of cause and effect? It’s a fascinating question outside of the scope of our film, but one we would love to figure out someday.

FB: The resistance to photography as art and the resistance to homosexuality as an “acceptable lifestyle” were both about denying reality. Perhaps post-WWII, our culture has increasingly faced reality. People are gay and photography can be art. Allowing for both makes life better for everyone (except for bigots and snobs).

Vanity Fair remarked: “Robert really saved Sam Wagstaff’s life. At the beginning of the ’70s, anyone who knew Sam said that he was virtually a recluse. Robert is the one who got him interested in collecting photography. Sam revolutionized the way we look at photographs. When he sold his collection to the Getty Museum, his position in photography was forever assured.” Can you talk a bit about their relationship, the generational differences and how, if at all, Sam affected Robert’s work?

RB: It was a very complex and layered relationship; and in that respect like any real true relationship. People like to judge and say Mapplethorpe used Sam, but we feel it was a truly symbiotic relationship.

FB: The way we see it is that Sam took the initiative (calling Mapplethorpe on the phone to introduce himself) but Mapplethorpe led the way. He needed Sam to champion the medium he had chosen. Mapplethorpe could say it was art but people needed to hear it from a respected curator and collector before they took photography seriously. Wagstaff was perhaps Mapplethorpe’s most brilliantly strategic hook-up. And they genuinely loved each other. It might be complicated – perhaps more complicated than we can grasp – but that doesn’t make it any less true.

How do you both think a younger generation will react to Mapplethorpe, given the ubiquity of cameras, camera filters and 24/7 sexuality? What perspectives can/should they bring?

RB: Well, you can arguably see Mapplethorpe as a pioneer of sexplicit selfies. He was also into recognizing the male body as an erotic form the same way the female nude has always been revered in art history. Would Calvin Klein’s groundbreaking Marky Mark campaign have existed without his groundbreaking work?

FB: At the same time the tsunami of similar kinds of imagery only goes to show how unique Mapplethorpe’s vision was back then, and remains so today. You can spot it immediately and there is nothing like it. While some of his contemporaries and predecessors were working in a similar area, he is the one we remember today. That’s no accident.

What would each of you say is the best representative of Mapplethorpe’s work and why?

RB: For me it’s not necessarily the photographs but the early collages with spray cans and cut-up porn. They are so raw, immediate and beautiful. But you have to look at all the work which is what makes the amazing retrospectives curated at LACMA by Britt Salvesen and The Getty by Paul Martineau such essential viewing.

FB: Mapplethorpe said that the life he was leading was more important than the pictures he was taking. His life was the work of art. I think we discovered that making the film, and it was his ultimate masterpiece. He lived his best life before Oprah coined the phrase. It’s inspiring: Life is a work of art, so value it and live it as such!

Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures is available on HBO GO. For more information visit mapplethorpefilm.com