Longtime community leaders will receive lifetime achievement awards.

The planning committee for San Diego’s seventh annual Harvey Milk Diversity Breakfast may have a disagreement with one of their honorees.

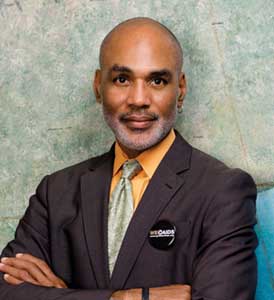

Phill Wilson, the president and chief executive officer of the Black AIDS Institute who is being honored with the Harvey Milk Lifetime Achievement Award, doesn’t believe his work has been exceptional.

Attendees at the event will also likely disagree after they hear Wilson speak at the event, scheduled for Thursday, May 21 at the San Diego Bayfront Hilton.

“For various reasons, I am being retrospective of my life and conscious of my own mortality,” Wilson said. “I am honored and humbled to be in the company of Rev. Perry, Nicole (Murray Ramirez, one of the event’s founders) and the memory of Harvey, it’s also always with a sense of queasiness about being worthy of honor or recognition.

“I don’t think what I do, or have done, is exceptional. I’ve been part of a community that has been under attack. This is what I should be doing as an openly gay black man living with AIDS in the 21st century,” Wilson said. “We should be fighting for a better world; fighting for a more inclusive world – one that doesn’t simply tolerate us, but acknowledges us as integral and recognizes our gifts are extremely valuable. That’s the world we should be fighting for. That’s the price of the ticket.”

Milk, who had moved from New York to San Francisco’s Castro neighborhood, was elected to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors in 1977, making him one of the first openly gay candidates to be elected to public office in the U.S. His life was cut short when he was assassinated, along with San Francisco Mayor George Moscone, Nov. 27, 1978 after only 11 months in office. He was 48 years old.

“Harvey’s story was instrumental in my coming out story,” Wilson said. “I came out in 1980, and one of the first gay people that I read about was Harvey. He became even more important when I moved to California in 1982.

“When Prop. 64 happened (a 1986 ballot measure which proposed a quarantine of all people with HIV), we all looked at Prop. 6 (the Briggs Initiative, which would have banned gay and lesbians from working in California public schools) and the role he played (Milk was one of the campaign’s most visible and effective spokespersons). We modeled our work on that work,” Wilson said. “For me, it was not as much that he was elected, the power of Harvey’s story to me was much more connected to the sense of responsibility; the understanding that if change is going to happen, we’re the ones who are going to have to make it happen.”

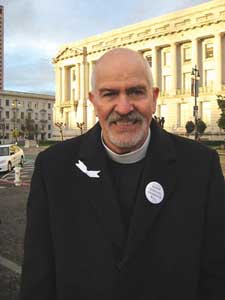

Perry learned some additional lessons from working on the Briggs Initiative with Milk.

“He would go into Orange County and places no one else wanted to go. He always tried,” Perry said. “I think he was also a bit of a loner in some ways. With Briggs, he would say, ‘I’ll do everything I can do. I don’t need to be on the committee to do it.’ And he always followed up.”

“I learned about being strategic and understanding, very early on, that we needed to reach out beyond our comfort zones,” Wilson said. “Those lessons manifested in my life; in never waiting for someone else to do what I could do; to leading where you can lead. Harvey was instrumental to me in that way, and Troy and Nicole have been as well. They have clearly lived the values of walking in your truth and trying to make a difference.”

San Diego’s Harvey Milk Diversity Breakfast, one of the largest celebrations in the nation honoring the slain civil rights leader, was launched seven years ago by Nicole Murray Ramirez, Robert Gleason and the San Diego LGBT Community Center. The event regularly draws more than 1,000 San Diegans to honor and celebrate the life and work of Harvey Milk.

“The Harvey Milk Diversity Breakfast is a great opportunity for our community and our partners to come together to honor the legacy of Harvey Milk and to recommit ourselves to the social justice work that remains to be done,” said Dr. Delores A. Jacobs, chief executive officer of The San Diego LGBT Community Center. “It allows us to take a few moments to reflect on recent victories, challenges and to celebrate those in our community who have been inspired by Harvey Milk, and who have helped turn some of his dreams into realities.”

This year’s event will also feature a performance by the Martin Luther King Jr. Community Choir San Diego, also known as the MLK Choir.

“We are deeply honored to have the opportunity to recognize Rev. Troy Perry and Phill Wilson for their many contributions to the LGBT community, as well as people of color, faith and HIV/AIDS communities,” Jacobs said. “For decades, Troy and Phill have committed themselves to lives of service, and these awards are a simple, but sincere way, for us to recognize and show our respect for their courage, vision and dedication.”

Rev. Perry is the founder of the Metropolitan Community Churches (MCC). What began in 1968 as a service for 12 people in his Southern California living room has grown over the past 47 years to a church with a membership numbering over 43,000. He first met Milk at his camera shop in the Castro.

“I met Harvey after he ran the first time. He didn’t win the first time, but you could tell he was going to be somebody important; that drive, that ambition was there,” Perry said. “When he was elected, I flew up to San Francisco and was there for his swearing in.”

Perry was finishing a speaking engagement in Canada when word came of Milk’s assassination.

“I thought they must have been kidding, but then I started to believe it could be true. I was trying to find an American radio station, and then I called back down to my office. They said, ‘Troy, we’ve been trying to reach you.’ I knew then that it was true. I flew back to L.A., got a change of clothes and got on another plan and flew up to San Francisco. It was so sad,” Perry said. “To this day, I always remember Harvey. He was our first martyr. It’s such a shame. There was such promise there. It’s so sad to me that he didn’t live to see all that’s transpired.”

Perry has played an important role in the progress that has transpired. Never content to limit his voice to the pulpit, he – along with Morris Kight and Bob Humphries – founded Christopher Street West, the Los Angeles LGBT Pride Parade. Perry was the first openly gay person to serve on the Los Angeles County Commission on Human Relations.

Rev. Perry was invited to the White House by the administration of President Jimmy Carter to discuss gay and lesbian civil rights, and was appointed by President Bill Clinton as an official delegate to the White House Conference on Hate Crimes and the White House Conference on AIDS. President Barack Obama invited him to the White House in 2009 for a commemoration of the 40th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots.

He has long been a champion for marriage equality, not only performing ceremonies as clergy, but taking the fight to the courts. In 2003, he and his spouse, Philip DeBlieck were married in Canada. In 2004, they filed suit against the State of California seeking recognition of their marriage. On June 16, 2008, the California Supreme Court ruled in their favor, helping launch the 2008 “summer of love” where same-sex couples could marry in California before being halted by the passage of Proposition 8.

He is also the author of The Lord is My Shepherd and He Knows I’m Gay, Don’t Be Afraid Anymore and 10 Spiritual Truths for Gays and Lesbians* (*and everyone else!).

Wilson began his activism in earnest in the early 1980s when he and his partner, Chris Brownlie, were both diagnosed with HIV.

He was a co-founder of the National Black Lesbian & Gay Leadership Forum and the National Task Force on AIDS Prevention. He was involved in the founding of the Chris Brownlie Hospice, named for his late partner, as well as the AIDS Healthcare Foundation, the National Minority AIDS Council, the Los Angeles County Gay Men of Color Consortium and the CAEAR Coalition.

Wilson launched the Black AIDS Institute in 1999, the only national HIV/AIDS think tank focused exclusively on Black people, to stop the AIDS pandemic in Black communities. Prior to that, he served as the AIDS Coordinator for the City of Los Angeles; the Director of Policy and Planning at AIDS Project Los Angeles (APLA); and co-chaired the Los Angeles County HIV Health Commission. He has been an appointee to the HRSA AIDS Advisory Committee, and served on the Presidential Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS.

He has also served as the coordinator of the International Community Treatment and Science Workshop at the International AIDS Conferences in Geneva, Durban, Barcelona, Bangkok, Toronto and Washington, DC.

Wilson was a member of the US delegation to the 1994 World AIDS Summit in Paris, and has worked extensively on HIV/AIDS policy, research, prevention, and treatment issues in more than a dozen different countries.

While Wilson may be circumspect about his own contributions, he does acknowledge that his work has been done in exceptional times. And that the legacy of Harvey Milk continues to play a role in his activism.

“Yes, the 35 years that I’ve been involved, it’s all been during exceptional times,” Wilson said. “The challenges and threats to the communities – and I use communities – the LGBT community, the HIV/AIDS community, the black community, the black LGBT community – all of these groups are unique and separate and they all have this intersectionality of what we have in common. We have collectively been under attack, but we have persevered and been victorious. We have survived and thrived. And, along the way, we have contributed to a better understanding of humanity.”

Wilson looks forward to the San Diego event, and believes such celebrations are important in the movement.

“I do think it is important to look back and to be reminded of the fight and the trajectory that we’re on,” he said. “Commemorating these days provides us with an opportunity to constantly assess, validate and verify where we are; to seek out the North Star that guides us and figure out where we need to go. I hope these events inspire folks to walk in their own truth and to raise their hands when the call goes out to them. We only move forward when folks step up and do the work.

“What I hope the legacy of my work, and definitely of Harvey Milk’s work, is that anyone can do this,” Wilson said. “Harvey was just a schmuck who stood up when someone needed to stand up. I’m just a schmuck who has stood up. Anyone can do this work. Everyone is obligated to do what they can. As Martin Luther King said, ‘Everybody can be great because anybody can serve.”

Perseverance is a key element of what Perry recalls as part of Milk’s legacy. And it’s also what he hopes will be part of his.

“Well, he had to run three times to get there, but he kept at it,” Perry said. “I’ve seen people who’ve come and left, but he tried so hard to win that office and he finally did.

“I always hope that people will say Troy Perry was fearless and faithful. He did all he could in his life to make things better. I never wanted to be a shooting star, I wanted to run the race,” he said. “I have wanted to make sure that we have every right that every other American has. I’ve worked with politicians and with religious leaders and I always tell them, ‘I want all the rights that our Constitution has for all Americans. I don’t want any more, but I’ll be damned if I’ll accept anything less.’”