As we celebrate our significant gains in LGBT equality over the last year, I cannot help thinking about the many LGBT heroes who are all too often forgotten. A friend who was at the film Milk in Hillcrest heard a young gay man say after the movie “I loved it but why did they have him die at the end”?

Our LGBT history is often forgotten or not celebrated. This is why it is important to teach our history in every public school in the nation. California lawmakers have made teaching LGBT history mandatory but the implementation in schools has been abysmal at best.

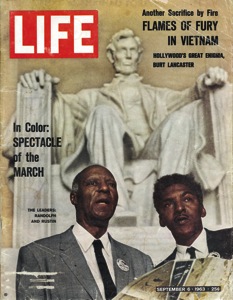

The person who most embodies our forgotten heroes is Bayard Rustin. Ninety eight percent of people reading this just said to themselves “who is Bayard Rustin”? If I told you that an openly gay African American man was the architect of the historic 1963 March on Washington, would you believe me? Or that he was on the cover of Life magazine that same year?

The 1963 March on Washington is so closely associated with Dr. Martin Luther King that many simply refer to it as King’s march. Nothing could be farther from the truth.

So who was Bayard Rustin? He was an openly gay man who was a leader in the peace and social justice movements of the 1940s, ’50s, ’60s, ’70s and ’80s. Back in the day, social justice was primarily focused upon civil rights for blacks, but also included Latino and LGBT rights.

While many people believe that Rosa Parks was the first person to refuse to give up her seat to a white person on a bus, more than a decade before, Irene Morgan did the same when she was traveling on a bus between states. In 1948, her court case resulted in the Supreme Court ruling that blacks could ride up front as long as they were travelling between two states. Bayard Rustin led a group to test the court ruling.

Riding with other white social justice supporters, Bayard and other blacks went to North Carolina, got on Trailways and Greyhound buses together and rode up front. They were beaten and jailed on a technicality; they got off the bus for an overnight stay before it crossed state lines, although they were travelling to Tennessee. Bayard was sentenced to twenty-two days on a chain gang.

Bayard wrote a series of articles in the New York Post about the horrible conditions during his prison stay that led to the abolishment of chain gangs in North Carolina. Did I mention Bayard was openly gay?

Can you imagine being openly gay in the 1940s and ’50s? It speaks volumes about Bayard’s talent as an activist in the peace and social justice movements that his “homosexuality” was ignored or overlooked because he was the best man for the job. This was particularly apparent when it came to the 1963 March on Washington.

Largely due to his homosexuality, leaders within the black community like Martin Luther King, labor leader A. Phillip Randolph, Whitney Young of the Urban League, Roy Wilkins of the NAACP and others, had a heated discussion about whether Bayard should head the march. Bayard had been arrested earlier for having sex in a car with two men and was therefore convicted on a morals charge.

Ultimately, black leaders decided Bayard’s abilities outweighed the perceived harm his homosexuality could do to the civil rights movement. A compromise was struck and A. Phillip Randolph was the “official” head of the march and Bayard was his deputy director. To borrow a phrase from Dr. King, Bayard was not judged by his sexual orientation, but by the content of his character.

The 1963 March on Washington was a resounding success with more than 250,000 people in attendance. It became the blueprint for all protests in Washington since, yet very few in our community know Bayard Rustin’s name. The great organizer and a forgotten hero.

There are so many others that have done so much but have been relegated to the historical trash bin. It is time that we begin celebrating people like Henry Gerber, Harry Hay, Jose Sarria, Barbara Gittings, Frank Kameny, Lorraine Hansberry, Cleve Jones, Elizabeth Birch, E. Lynne Harris, Phyllis Lyon and Del Martin, to name just a few. Do yourself a favor this Pride season and Google these names, as well as “LGBT history,” you just might be surprised at all of the wonderfully talented LGBT heroes that often get forgotten.

Stampp Corbin

Publisher

San Diego LGBT Weekly