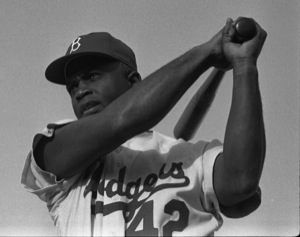

- Jackie Robinson in Dodgers uniform, 1954

April 15 marked the 66th anniversary of Jackie Robinson becoming the first African American to play Major League Baseball. Most years, this wouldn’t cause a ripple in an LGBT community focused on the bizarre hurdles they face in tax law. This year, however, the anniversary came with 42, a new biopic of Robinson’s journey; and in the wake of the Supreme Court gay marriage cases and the reported plans of up to four gay NFL players to come out, that nexus prompted many to ask, “Who will be the gay Jackie Robinson?”

It’s an important question, as Robinson was a singular man who handled a nearly impossible situation with dignity and poise. The better first question, however, may be “Who will be the gay Branch Rickey?” Rickey, played in 42 by Harrison Ford, was the white Brooklyn Dodgers executive who committed to finding the right player to break the color barrier. In most versions of the tale, Rickey wanted to integrate baseball because it was the right thing to do, the right time to do it, and it was good business. All are currently true about eliminating baseball’s taboo on openly gay players, but no one seems to be jumping on the opportunity.

Those who don’t believe that having an openly gay major leaguer is the right thing to do, like those who opposed Rickey and Robinson, will likely accept no teacher but history. So there’s little use arguing the point.

Is it the right time? Consider America in 1947. The military was still segregated. California was still a year away from overturning its ban on interracial marriage. Brown v. Board of Education, the decision integrating schools, was still 7 years away. The Civil Rights Act was 17 years away. In many ways, LGBT equality is ahead of where racial equality stood in 1947, suggesting that American baseball fans will have less problem with a gay player in 2013 than they did with Robinson 66 years ago.

The business case is different, but in the end remains compelling for equality. Rickey’s reasoning included a desire to have first dibs on stars from the Negro Leagues where Robinson and others played. There is no analogous talent pool from an “LGBT League” to flow to the team that breaks the dam. However, there are no doubt LGBT players who might factor a supportive team into free agency negotiations, and those who might play better if their focus weren’t split on hiding who they are.

Rickey’s analysis also involved tapping into the African American fan base, and here the case is strikingly similar. LGBT Americans have nearly a trillion dollars in buying power, often with more discretionary income than straight counterparts. Those extra dollars are available for entertainment, such as travel, movies and sporting events. Corporate sponsors, who might have been a barrier in years past, now flock to equality causes.

In fact, the first team to aggressively tout tolerance could likely access many of the financial benefits without an out player. Imagine a Branch Rickey from the Padres, perhaps during Out at the Park, issuing the following statement: “The San Diego Padres appreciate the support of our LGBT fans, and want them to know that the Padres organization does not tolerate discrimination at any level. As part of our commitment to employment non-discrimination, we have instructed Padres executives, managers, coaches and scouts to make it clear that openly LGBT baseball players are welcomed in our organization.”

The team would be the lead story on ESPN and own the mainstream media cycle that day. Whatever becomes the LGBT-Padres logo would light up Facebook like a red equals sign, and the associated jersey would sell out. Viewership might spike enough to make Time Warner Cable carry the games.

As with DADT repeal, concerns about a backlash would prove to be overrated. Rumors of a mass player exodus won’t materialize, for professional and financial reasons. Statements of condemnation from Focus on the Family and the National Organization for Marriage would be quickly countered by politicians and LGBT groups. Shockingly, the games look the same except for signs with different views on the issues. A few season ticket holders demand their money back and would be replaced by more LGBT fans.

All of that before the first the player comes out of the closet. Like Robinson, that player will need infinite patience with the jeers of fans and teammates, a spine of steel for threats against him and his family.

Like Robinson, he, not an executive, will be the true hero of the story. But not the whole story.

There is a place in history for an LGBT Rickey, someone who steps up to the plate to create a better chance for that player, while seizing a golden opportunity for their team, and baseball.

He or she won’t ever have every MLB player wearing their number, but they’ll be remembered, like Rickey, for proving that “… prejudice has no place in sports, and baseball must recognize that truth if it is to maintain stature as a national game.”