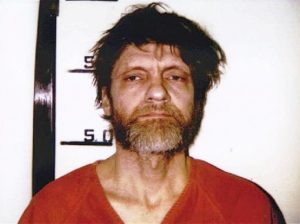

The Unabomber miniseries on The Discovery Channel has brought back uneasy 1994 memories. Unabomber Ted Kaczynski had sent 14 bombs by the end of 1993 and another deadly bomb in December 1994.

I was a government official in the summer of 1994 when Republican North Carolina Sen. Jesse Helms (1921-2008) bashed me in a speech broadcast over CSPAN, printed in the Congressional Record, and covered by the mainstream media. I held a formal appointment authorized by the Clinton administration to promote workplace fairness in government agencies. Dozens of reporters phoned my Washington office for interviews.

My government agency demanded I refuse all interview requests for fear of further angering Sen. Helms and creating budget difficulties and political problems with nominations for department positions before Congressional Committees on Capitol Hill. I was bullied into silence at a critical time for LGBT employment issues. The silence did not serve the LGBT community well at that time and the Clinton administration’s explanation to Helms about my appointment harmed the community’s work for employment equality at that time and now.

After the Helms Senate bashing I received threatening notes on my office desk, threatening calls were made to my office and home telephones, my car window was broken out and threatening letters arrived at my home in Northwest Washington. With news reports of mail bombs sent by the Unabomber, anonymous mail began to bother me. I was not suspicious the Unabomber would target me, it was a Washington, D.C.-area copycat bomber I feared. A bomber motivated to violence by the hateful words of Jesse Helms.

During the summer and fall of 1994, I received hundreds of calls and letters from LGBT government employees across the country. They all had a reasonable question: Was it safe for them to come out and would their federal agencies protect them in the event of discrimination.

I received calls from federal personnel in Forest Service, Agricultural Marketing Service/Food Safety Inspectors (meat inspectors in the traditional sense), FBI, Foreign Commercial Service, and statisticians, economists, secretaries and other professionals across many federal agencies. It was a late-night telephone call from a man who identified himself with the Agricultural Marketing Service that disturbed me most.

The man explained he worked in an animal slaughter facility in the Midwest and he wanted to come out to his co-workers and supervisor. He wanted to know if I felt it safe for him to do so. I explained to him that despite the fact the U.S. Department of Agriculture committed to a nondiscriminatory workplace for LGBT workers, enforcement of this policy was largely untested in Washington and I could not advise how his Midwest supervisors would react. I told him he would have to make the decision after talking with his HR office and his union representatives.

At the end of our phone conversation, the guy told me he had prepared a heavy envelope of documents on his employment situation. “It’s a box really,” he said. What he said next, frightened me. “I’d like to mail it to you without a return address.”

He was concerned about his supervisors seeing his name on the box. He already had my home address he said. I had not given my address to him and I asked how he had gotten it. He said a friend in Washington had given it to him. He did not want to reveal his friend’s name.

I was cold by this point and imagining a copycat Unabomber inspired by Sen. Jesse Helms. His Washington friend might be a staffer for Helms, I thought. My primary concern was for my safety. My secondary concern was for my workload.

My government and home desks were covered in paper already. How could I manage anymore work?

I advised the Midwest caller against mailing me his box of documents. I advised him to send it to his agency and to review it with his personnel office. He insisted he needed to mail his box of documents to someone else. He insisted on sending the box to me. Suddenly, I thought of the perfect person the guy could mail his box to: President Bill Clinton.

I told him President Clinton had staffers who were dedicated to LGBT issues. I had worked with them myself and I told the guy they would know just how to advise him about coming out at his Midwest government location. I wished him the best and ended the call.

The White House mail was perfectly safe in 1994 and today. No dangerous mail will ever make its way to the president of the United States.

I never heard from the guy again. I do not know if he was a copycat Unabomber inspired by Sen. Jesse Helms or a genuine gay government employee looking for workplace guidance. I am certain I directed him to the correct place: The president of the United States. At the time, all LGBT federal workers were looking for guidance from the president. I was among them.

End note: In December 1994, a mail bomb from Unabomber Ted Kacznyski killed advertising executive Thomas J. Mosser at his home in North Caldwell, N.J. Recluse Kacznyski was captured in the Montana wilderness in 1996 and he is now serving eight life sentences without possibility of parole at a supermax prison in Colorado.

Jim Patterson is an economist, retired U.S. diplomat and career Foreign Service Officer based in Washington DC. JEPDiplomat@gmail.com