The veterinarian called to say he would be 10-15 minutes late and I thanked him for the professional courtesy. I was especially grateful for the additional time with Brady, my four-legged companion. The last few hours together were passing too quickly and the extra few minutes were a gift. I hung up the phone and pulled another tissue from the rapidly depleting box.

Our lives changed the day we met Brady at the San Diego County animal shelter. For one thing, we went on miles of walks.

I grew up with dogs, family pets as well as working dogs, retrievers and herders, but had been a “cat person” most of my adult life. Because cats prefer being alone and don’t mind if their human leaves for the weekend. But our home felt empty after “Desiree”, a regal 15-year old long-furred feline, was laid to rest. Our house was near the beach with a large fenced-in backyard. Perfect for a dog, my partner and I reasoned. We began our search online, scanning the Animal Services Department’s pets available page. Weeks passed as we discussed the pros and cons of adopting a dog. Were we ready for the commitment a dog requires? Were we prepared to be good guardians? The debate was resolved and we found ourselves at the South Bay shelter with a list of candidates in hand.

The bright-eyed young male in the first cage, medium-sized with curly black fur and a white blaze on his chest, wasn’t on our list; too newly arrived to have his mug shot posted on the adoption page, we were told. I try not to anthropomorphize pets, to ascribe human attributes to their behavior. However, I could swear he exuded a certain confidence and self-awareness, an assured I-know-I’m-cute-and-you’re-gonna-love-me posture.

We were told he was a stray, but wasn’t feral. He was one year old, more or less, and had been cared for at one time; he was a little shaggy, but in good health and understood basic commands. We were told he was a prior adoptee but had been returned by the family a week later; apparently he doesn’t do well with kids. We later discovered cats and squirrels were constant vexations, and he didn’t do well with other dogs while on leash. We were told he was a poodle mix which meant he was a very smart active “low shed” dog. Judging by the way he jumped into the truck, leapt up on the back of furniture, bounded onto bar stools, we decided he was a circus poodle mix.

We learned a few things as newly minted dog guardians. For instance, we learned our fence was not as secure as we thought. One day when Brady was supposedly in the backyard, I looked outside to see him sitting in the driver’s seat of the truck, as if he was ready for a quick spin around the block. He had escaped through a gap near the side gate and didn’t wander, but instead climbed through the truck’s open window and waited patiently. (Is it possible for a dog to have a sense of humor?) We repaired the breach and fortified the fence but I remember thinking, what a clever dog.

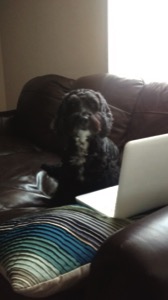

We learned more about our new charge’s personality, too. Brady was intelligent so he knew what was expected of him and how to behave. But he was also a willful dog, which meant he would sit on command, but only for a quick second or two. He would play fetch, but only until he grew bored. When Brady dropped the ball and ran crazy figure eight victory laps around the yard, a rooster tail of grass blades in his wake, we knew the game was over.

We also learned a dog, regardless of how adorably cute and intelligent he is, cannot save a crumbling relationship. When the dust settled, my ex moved out and Brady stayed.

Brady was my constant companion as the years passed. He was there when I lost the beach house during the Great Recession and moved to an apartment in the city. He’d wait for hours indoors while I was at the office. I imagined he enjoyed the time off, relaxing, off the clock. The best part of my day however, was when he’d greet me at the door with wild wags and a happy dance.

He was protective and preferred staying by my side on walks at the beach, or in the park. “Go play,” I’d urge. He would, but apparently “go play” means hump all the other dogs.

He would greet guests with enthusiastic barking until they sat down, and then he’d be their best friend. His purpose in life was to lick them on the lips. But if Brady didn’t like a guest, as has happened a time or two, they’d be asked to leave; you had to kick rocks if my dog didn’t like you.

Everything was fine until about a year ago when I noticed he was having trouble climbing up and down the stairs; he was hesitant, would paw at the first step and sometimes stumble. I mentioned this to his vet during a checkup and she said it might be his joints, add Cosequin to his diet. I soon discovered though, his problem with the stairs was not his joints; he was having trouble seeing the stairs. Within six months he was completely blind. And deaf.

Brady did not readily accept his new circumstances. There were times when he’d lay by my side and whimper and I could not console him. But he adjusted to his new reality. Having taken so many walks, the routes ingrained in his memory, he would choose our path. My responsibility was to help him navigate curbs and prevent him from walking into hedges, utility poles and street trees. He had a tendency to pinball down the sidewalk.

Then his digestive system began to fail. He became incontinent. I could not leave him alone for more than 2 hours. He didn’t eat often and when he did, he vomited what was consumed. He was only 10 years old (I thought we’d have more time together), but his quality of life was compromised. His future was bleak.

I consulted numerous people as I agonized about the final act of compassion. The stories they shared concerning the same struggle gave me strength and courage to proceed. Although he tolerated his annual checkups and shots and periodic probing, visits to the doctor’s office made him anxious; his final moments would not be apprehensive ones. I was referred to several in-home euthanasia services.

The clock starts ticking once the appointment is made. We only had ninety-six hours left together. The end was near and Brady was a dead dog walking.

I’d like to say Brady’s final days were a montage of joyful activities – of trips to the beach, of hours at the park, of big meaty steak bones to chew on – but the reality was different for a blind, deaf and incontinent dog. Our time instead was spent with hours of belly rubs and cuddles interrupted by short walks. He’d lick away my tears.

Brady acknowledged the veterinarian and greeted him without the usual display of barking. (Is it possible for a dog to be resigned to their fate?). He snuggled into my lap and stayed there during the procedure. (Is it possible for a dog to not only accept, but to welcome the end?) The veterinarian, with great care and respect, swaddled Brady’s lifeless body in a quilt and asked if I’d like to carry him to the car. I had anticipated the question and thought about my response. But, as Brady’s guardian, I really didn’t have a choice.

Of course I’d walk my buddy one last time. Slowly. Slowly.