“We were making out in my car and I reached down and felt something that wasn’t supposed to be there. Then I blacked out and the next thing you know there’s a dead body and I’ve got a hammer in my hand,” said Josh Vallum in a September 2016 prison interview while he was awaiting trial.

But after his trans panic story fell apart, Vallum said. “I killed Mercedes Williamson.” Vallum confessed in a Mississippi court Oct. 16. He said he killed the teenager because he “didn’t want it to come out” that he was having a long term relationship with a transgender woman.

The Transgender Day of Remembrance (TDOR) is a time to memorialize those who were murdered simply because they are transgender. The event has been held in November for nearly 20 years to raise public awareness of hate crimes against transgender people.

TDOR is a time we transgender folk and our allies come together to express love and respect for our people in the face of international antipathy. And TDOR also reminds non-transgender people that we are children, parents, friends and lovers.

Trans activist Gwendolyn Ann Smith memorialized the murder of trans woman Rita Hester in Alliston, Mass., in 1999, creating the first TDOR. Over time it has evolved into an international event held in approximately 200 U.S. cities and more than 20 countries.

TDOR usually includes the readings of names of the transgender people who were killed that year. Reflecting on when TDOR first began, Smith said in a 2014 magazine article, “Trans people were nameless victims in many cases. Our killers would do their best to erase our existence from the world. And law enforcement, the media and others would continue the job. We would be regularly, consistently misgendered and labeled with names we did not choose; that is, when we weren’t simply reported as an unknown man in women’s clothing.”

In 2016 there have been at least 23 transgender people murdered in the United States. Just last month, 32-year-old Brandi Bleadsoe of Cleveland, Ohio, was found dead behind an apartment building with a gunshot wound to the chest, head trauma and a plastic bag over her head. This past June in San Diego, four suspects on the run were arrested in Ocean Beach for the murder of 38-year-old trans man Amos Beede, who was found severely beaten at a homeless encampment in Burlington, Vermont. And in Mexico, there’s been a dramatic surge of violence against transgender people, among them: Paola Ledezma, Itzel Duran and Alessa Flores. Trans activists in Mexico blame their murders on hate stirred up by religious organizations publicly demonstrating against marriage equality for LGBT citizens.

Today our community is better organized and much more vocal than we were in 1999. When a trans person is murdered we make sure they are not forgotten. We no longer tolerate attempts to ignore and cover up violence against our people; and when our siblings are misgendered by the media, we make sure to correct them.

When our local trans community comes together at The San Diego LGBT Center, Nov. 17, the trans people killed in 2016 will be remembered. But what about the transgender people who were murdered here in San Diego before TDOR began? Who will remember them?

In December 1990, trans woman Tasha Santana was gunned down while on a pay phone talking with a 911 dispatcher. She had been robbed by two Marines from Camp Pendleton. Santana was telling the dispatcher, “Get this down. QCM 837. That’s the license plate. The police are looking for them right now, and they’re right here in front of my face at the Wally Johnson (Motel). Please come back and get ‘em.” The dispatcher then said: “OK, please hold the line for me.” Santana responded calmly, “Thank you,” and the dispatcher said again, “Hold on.”

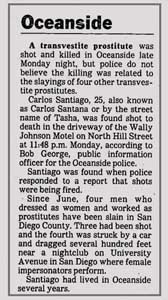

But it was already too late. After a pause of 43 seconds, an off-duty security guard reported that Santana had been shot in the chest. According to the San Diego Union quoting Oceanside police, “Santana, a well-known transsexual who was seeking a sex-change operation, died shortly afterward.” Oceanside police described her as a “transsexual prostitute.”

Santana’s murder capped a particularly violent year for San Diego’s transgender community.

Back in June 1990, two trans women were found shot in the head near the San Diego Wild Animal Park. The police dead-named (used their male names assigned at birth) the victims. But today, in this article, they will be respected. Ms. Ayala, 25, was taken to Palomar Hospital, where she died. A companion, Ms. Estabon, 23, was found dead in the brush a short distance from the roadway. And the disrespect didn’t stop with dead-names. They were treated by the media as public curiosities, not human beings who were tragically murdered. Newspapers described the victims as “two transvestites” and said that “police initially thought the victims were women, since they were dressed in women’s clothing” and that “hospital workers quickly discovered their patient was male, though he had enlarged breasts.”

July 2, 1990, in Normal Heights, Ms. Osuna, described as a “24 year-old transvestite,” was shot several times in the chest. Before she died, Osuna was able to identify her assailant “as a black man driving a dark-colored compact car.” Two months later on Sept. 4, Ms. Pierce was referred to in the police report as a “36-year-old man dressed as a woman and working as a prostitute.” Police said she was run down by a car and dragged half a block.” In November the badly decomposed body of a transgender woman was found near Sunrise Highway in the Laguna Mountains. Deputy Coroner George Dickason said the body was that of a transsexual with breast implants.

The victims of violence against our community were, and still are today, overwhelmingly transgender women of color. Often shunned by their families and forced to live on the streets, these women struggled to survive in dangerous environments where transphobia, racism and sexism often led to high rates of poverty, unemployment and homelessness.

When asked to comment as to why so many transgender people were being targeted in 1990, San Diego Police Department homicide Lt. Dan Berglund said, “Certainly, there is the hope that there will be no more deaths and that these deaths will not incite other people to the same thing. But as long as they continue to lead the same lifestyle, they will continue to expose themselves to risk.” Burglund said, “There is a heightened sense of danger among transvestites and transsexuals who work as prostitutes. These people understand that they are part of a small group, easily singled out for violence.”

They were victims, but in the eyes of society they caused their own murders. And with the exception of Tasha Santana, all the other murders that year have gone unsolved. Her killers were convicted of manslaughter and were sentenced to only 11 years in prison.

According to the latest worldwide survey by the advocacy group Transgender Europe, there were 2,115 murders of “trans and gender diverse people” in 65 countries between January 2008 and April 2016. Over 78 percent of those murders took place in Latin America. Brazil tops the list with 845 murders, Mexico is second with 247 and the United States is third with 141.

So how far have we come since the first TDOR back in 1999? While the spike in violence against trans people has actually increased due to more visibility and better reporting, there has been progress. Josh Vallum received a life sentence for murdering Mercedes Williamson. His trans panic defense fell apart when people stepped forward to dispute his claim; pointing out that Williams lived openly as a trans woman. And unlike decades past, Williams was treated by the media with the dignity she deserved, certainly better than the treatment our trans siblings received back in the early 1990s.

This year’s TDOR is Nov. 17 at The LGBT Center in San Diego. There will be a candlelight march starting at 6 p.m. The program begins at 7 p.m. followed by refreshments.

I guess that LGB lives aren’t worth remembering.