LGBT History Month Special Feature

Q&A with Sir Dermot Turing, biographer and nephew of WWII codebreaker Alan Turing

BY THOM SENZEE

Everyone called him Professor. But Alan Turing, the almost universally recognized father of artificial intelligence and modern computer science, was never actually a professor.

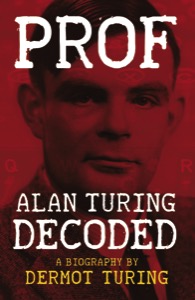

Yet who would begrudge Turing’s esteemed nephew, Sir Dermot Turing, for titling his biography, Prof: Alan Turing Decoded, a book that unravels the many myths that enshroud the story of his famous uncle as decoder of the previously unbreakable Nazi Enigma cyphering machine?

Sir Dermot Turing will be speaking in San Diego later this month hosted by San Diego Biomedical Research Institute. Details about how to attend follow at the end of the Q&A.

The 2014 film, The Imitation Game, in which Benedict Cumberbatch exquisitely plays Alan Turing, touched on a few of Turing’s lesser known accomplishments, such as his athletic prowess. Far from a physically awkward lad, Turing was in fact a jock. His nephew’s book describes the elder Turing’s athletic abilities and love of sport more robustly than the film could ever have done.

Dermot Turing’s book explores several previously unpublished sources, including British government sources released only since the last major biography about Turing was printed, as well as letters written by Alan Turing which just came to light in 2014. Then there’s Turing’s notebook which was rediscovered and sold in 2015 to which Sir Dermot was granted access along with Alan Turing’s brother’s archive of papers from 1954 when Alan Turing died by suicide. Turing’s death came shortly after he was convicted of the “crime” of having sex with another man. Queen Elizabeth II pardoned him posthumously in 2012.

Ninety years ago this year, Alan Turing arrived for schooling at Sherborne in the county of Dorset, England. No one then could have known that fewer than two decades later, during World War II, the fresh-faced, nominally closeted Turing was destined to alter the course of human events so fundamentally that the trajectory upon which his work would set computer science would continue to shape our technology well into the 21st century.

Dermot Turing, an accomplished mathematician in his own right, has been credited with humanizing and demystifying his uncle’s enigmatic life within the pages of the book now available on Amazon and in book stores everywhere.

“The succession of Alan Turing at GCHQ today continues to be inspired by his achievements in defense of his country,” asserts Robert Hannigan, who is the current director of Her Majesty’s Government Communications Headquarters. GCHQ is the same establishment, at the time located at legendary Bletchley Park, under whose auspices Alan Turing’s work to build an early computing device he called “Bombe” occurred.

But one need be neither a history wonk nor even a lover of spy stories to pick up a copy of Sir Dermot Turing’s biography about Alan Turing. As one of the United Kingdom’s most recent top spies, Sir John Scarlett, former head of M16 – yes, that’s the nonfictional agency for which the fictional James Bond, aka 007, spies – said about the book: “Prof makes a most readable contribution to our understanding of this exceptional man.”

Following is San Diego LGBT Weekly’s Q&A with Sir Dermot Turing:

San Diego LGBT Weekly: Although History Today book reviewer, Clare Mulley, couches your perspective of your uncle’s life as one derived only after his death, she calls Prof: Alan Turing Decoded a “cheerfully anecdotal account of a slightly grubby, surprisingly athletic, formidably clever and pleasingly humorous and humane man.” Is that a fair characterization of both your biography of your famous uncle and of the man himself?

Sir Dermot Turing: Yes, I think so. The thing about Alan Turing is that people perceive him as having been aloof, difficult to deal with, on another plane – and that is perhaps a bit unfair. I won’t deny that he was untidy and persistently defied social conventions, and that many things which interest regular people bored him. But who doesn’t know someone a bit like that? And I’m delighted that Clare thought my book was cheerful – the Alan Turing life story is definitely a tragedy, but there was lots of fun along the way, and it’s not so technical that we can’t all of us share in it.

How large does the legend of Alan Turing loom among members of the Turing family today?

When I was growing up, essentially no one had heard of Alan Turing outside the fields of pure mathematics and computer science. So mercifully I escaped comments at school like ‘ought to do better, with a name like that.’ Fortunately, so it seems did my own children, but by the time they were at school in the 1990s and early 2000s Alan Turing’s reputation was growing. I think this was largely because the U.K. government embarked on a major release of secret wartime papers about Enigma codebreaking at that time, and also at the same time there was this shift in people’s working patterns. Every office worker suddenly had a computer on their desk. Computers became something you can’t live without. And, because of Alan Turing’s personal story, brought to the wider public through various films and TV shows – The Imitation Game in particular – nowadays everybody has heard of him. So that’s great, because I no longer have to spell my name when I check into hotels.

Might there be another Alan among your ranks? Put another way, do other Turings show scientific or other academic prowess and/or promise akin to that of your famous uncle?

I’m bound to offend someone here. But I think, in all honesty, no. His was a pretty difficult act to follow. None of us has any pretensions to match even one of his achievements. But it’s perfectly fine not to be sparklingly clever all the time!

What facts did you learn from the previously unavailable papers to which you were granted access, especially regarding the obstacles, both political and technical, Alan Turing faced during those heady days at Bletchley?

I was very fortunate in that GCHQ – the UK Government facility that inherited the activities of Bletchley Park, and is the present-day UK counterpart of the NSA – allowed me a privileged preview of some recently declassified papers relating to Alan Turing’s activities in the second part of World War II. This period had always puzzled me, because Alan’s work on Enigma, and codebreaking more generally, had been largely completed quite early on in the war, so I really wanted to know about the 1942-1945 period. I knew he had worked on a machine for encrypting phone calls, but was that it? After all, Alan Turing was no engineer, even though he loved to roll up his sleeves and have a go. But his own technical skills were rather chaotic; so he had delegated the practical side of development to his colleagues. So what else had he been doing? The new GHCQ documents showed he’d been given a new role in information security. The most interesting aspect of this is when, just after the German surrender in 1945, he was sent to Germany to check out a top-secret lab where the Germans had been doing all sorts of cutting-edge work, including their own phone call machine, but also high-grade encipherment machinery and building their own prototype computer.

What discoveries in your research surprised you most?

I learned lots I hadn’t known before, but the thing that completely changed my perspective was going through the records of the Assize Court that convicted Alan Turing for gross indecency in 1952. I hadn’t realized until I went through the files that gross indecency cases were a kind of daily bread for the courts in those years. There were at least three other pairs of gay men who were tried at the same time as Alan Turing, and these cases were occupying about a quarter of the court’s time. The other peculiar aspect of the trial that I discovered was that the legal device to keep Alan Turing out of prison was to treat him as a mental case – in the twisted view of the early 1950s because he was gay that was a route open to them – and it’s that that led to him being given the course of hormone “therapy.” I don’t think any other biographers have really explored the legal aspects before, probably because the outcome itself is striking enough.

Do you have any thoughts on what greater advances in A.I. might the 1950s and ‘60s have offered had Alan Turing lived?

I think by 1954 Alan Turing had moved on from artificial intelligence and computing questions. What many people don’t realize is that by 1950 he had rekindled an interest in developmental biology. He was using mathematical models of how biochemicals might diffuse through growing tissue and give rise to asymmetric patterns, like you see on animal-skins or in various plant formations. At the time of his death he was trying to fit his theory to the Fibonacci numbers that you can find in, for example, the array of seeds in a sunflower head. So I think he had left A.I. to others by this stage. Who knows what Alan Turing would have gone on to tackle after biology.

What are your duties as a trustee for Bletchley Park; and what if any special role do you offer as perhaps a living vessel or amplifier of the legacy of your uncle’s imprint on the institution?

It’s a privilege to have been invited to serve on the Bletchley Park board, but the reality is that this is a not-for-profit operation turning over several million pounds a year, so the board’s role is to keep the business on the rails, to deliver a great experience for our visitors, and to keep a firm eye on the future so we continue to remain relevant for future generations. Alan Turing is a great draw and his name encourages visitors to come and find out more about what was achieved at Bletchley Park during World War II and how it made a difference. We also hope to raise their curiosity about present-day issues around communications security.

Is it possible that Alan Turing would be a willing and out-of-the-closet role model for young LGBT people had he been born 50-60 years later?

Alan Turing struggled, I think, with his sexuality, and in the climate which I described of post-war attitudes, he wasn’t particularly open about it except when he knew he was in safe company. For example, my father didn’t have the first idea his brother was gay until his arrest in 1952 – by which time Alan was nearly 40 years old. People also tell me that he was painfully shy and uncomfortable outside the academic classroom with standing up and being the leader. So, I suspect the answer is that he wouldn’t have wanted to be one of the first to come out – but it’s difficult to know, since coming out in the 1950s was just not an option, unlike later on. I am absolutely sure that he would have rejoiced in the change in social attitudes since then.

What then should young LGBT people – perhaps especially those interested in the sciences – take from his story and from your telling of it in Prof: Alan Turing Decoded?

I’d say that Alan Turing can be a role model for geeks everywhere. He was never ashamed of being a geek – and we all know that kids at school can be social misfits if they seem to be too interested in “difficult” things. Alan – and, to give credit where it’s due, his schools – were OK with not being mainstream. And not being mainstream might mean you have something special to contribute. So, we can celebrate diversity and tolerance, and get the best out of everybody.

What is the most important lesson to be taken from your book?

People who enjoyed The Imitation Game or who have seen other dramatic representations of Alan Turing or Bletchley Park might find that the real story isn’t quite the same as they might imagine, but every bit as good.

Sir Dermot Turing will speak at the Landmark Hillcrest Cinema the evening of Thursday, Oct. 27 at 7 p.m.

What question do you hope someone will ask at the forum Oct. 27?

People should feel free to ask about anything at all. But maybe the interesting questions are about where Alan Turing’s ideas came from. They didn’t arrive in his head as fully-formed masterworks fresh out of the ether. And looking at how his theories took shape can be as inspiring to all of us as his life-story.

What is your connection to the San Diego Biomedical Research Institute?

The Institute is led by Dr. Joanna Davies, who was a contemporary of mine when we both studied at Oxford University in the U.K., too long ago to mention without being impolite. I’m delighted she asked me to appear on this occasion.

Do you have have any idea what Alan Turing might have thought of the work the institute does?

It’s difficult to speculate, but I think it’s highly significant that Alan Turing’s last research student, Professor Bernard Richards, joined Alan’s lab in 1953 because he was a pure mathematician who wanted to work on Alan’s morphogenesis equations. Bernard Richards subsequently moved wholeheartedly into biology and medicine and developed his career in biomedical research. So – in a very indirect sense – the type of work being done at the Institute can claim some parenthood from Alan Turing.

Is there anything you would like to add?

Just to say thank you very much for the opportunity to discuss these things with you. Alan Turing is about so much more than Enigma codebreaking and it’s great to have the chance to talk about some of the other facets of his life and career.

San Diego Biomedical Research Institute will host Sir Dermot Turing for a community discussion and screening of the Oscar-winning film, The Imitation Game.

The forum will occur Thursday, Oct. 27 at 7 p.m., Landmark Hillcrest Cinema, 3965 Fifth Ave. in San Diego. Tickets are $20 and available via Eventbrite here. All proceeds benefit studies and other programs at San Diego Biomedical Research Institute.