The only information I had on old gay people when I came out was that we were doomed to be alone and thus miserable. Oh, and lesbians would have leathery skin while gay men would become pitiful predators.

At least, that’s how old perverts were portrayed in the pulps, and in non-fiction about criminology and juvenile delinquency.

First off, let’s define “old.” I’m 70 and happier than I’ve ever been. If you’re under, say, 64, you think I’m old. If you’re over seventy you think I’m a spring chicken. One of my Tai Chi instructors is 80, the other is 88. My best friend is 81 and still writing novels. It’s impossible to define old.

I couldn’t look leathery if I tried, nor could any of the dykes or gay men I know. I’ve seen plenty of people who might be described that way, gay or not, but they’ve usually spent years broiling in the sun on beaches other than Fire Island or Herring Cove in Provincetown.

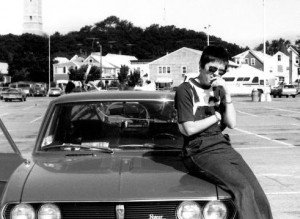

It’s funny how, most of my life, perfect strangers recoiled at the sight of my androgyny. With white hair I’ve become invisible, even to other dykes. Where once I’d get a smile or nod of recognition in the street in response to my own, the gaze of younger lesbians slides right off me, like I’m a lamp post or a (shudder) straight person.

In my 30s and 40s, I made up old lesbians in my stories. Perhaps I was looking for my elders. There may have been many around, but the generations before me were so very closeted I was aware only of a vacuum.

Once I got to know some actual true-to-life old dykes, I totally forgot there was an age difference. They treated me as an equal and we developed long, respectful friendships.

But I did such stupid stuff as a kid, made such risky, reasonless decisions, I could have used the guidance of an old dyke. In those younger years I was Alice falling down one rabbit hole after another.

Could I have learned from old lesbians and gay men or would my eyes have slid away from them the way baby dyke eyes do from me? Would I have listened? Yes, I was like that, very respectful of experienced people. As a matter of fact, I longed for such counsel, or at least for tales from people like me.

Would I have used their hard-won knowledge? Would I have followed recommended paths? I have no doubt I would have—and asked for detailed maps.

Would old gays have given me the kind of advice I needed? It would have been tricky for them to even associate with gay kids. Say I doctored my birth certificate (which I most certainly did) so I could go to gay bars. Say Joe Gay or Josie Gay, age 64, taught me how. Say my mother, a teacher, found out, or, worse, the bar was raided. Could Josie or Joe trust that this scared child would withstand a browbeating aimed at naming names?

Very few of us have biological or adoptive lesbian mothers. Where can we find guidance for our early gay adulthood? A local physician calls our mutual friends, the pianist and the handydyke (both 70 plus), her lesbian mothers. The pianist tells of the day a younger woman rushed up to her in the grocery store and announced that she and the handydyke were her lesbian aunties. The pianist knew another young lesbian, in the military, who had her suicide carefully planned out until two gay men stepped in to save her life. She also talks about a student, a homeless high school lesbian who lived with her and the handydyke for a year and who once said, “I wonder what an old lesbian looks like?”

There’s an obvious crying need for links between our young and old. The Old Lesbian Oral Herstory Project,* started by Arden Eversmeyer in 1997, seeks to document our lives. Books published by the project offer our stories. I would have devoured every word right up into my thirties, looking for who I was and who I could become.

The Trevor Project has a huge presence on Twitter that seeks to encourage gay and transgendered kids.

Reportedly, 40 percent of homeless youth are LGBT. They so need adults to model themselves after, ways of living gay to try on, in order to find themselves. Some have lost their families; some have families to whom they’re unable to relate. Who can hold their hands when they’re slipping on the icier, dicier spots of life? In whose footsteps can they follow on the paths of relationships?

There are more and more visible role models: Edie Windsor, Del Martin, Phyllis Lyon, Ellen Degeneres, Greg Louganis, Anderson Cooper, Janis Ian, who give gay kids something to strive for. But what about the non-celebrities, the lesbian Boy Scout leader, the gay male crossing guard, the hairdressers and auto painters, the farmers and pilots—how do we get them into the lives of lost children, lgbt college students, young gay barflies? Wouldn’t any of us, even now, love a gay grandparent who could teach us to garden or build a boat and rap our knuckles, or at least warn us, at any age, when we leap into the arms of ridiculously incompatible lovers?

The good news is that now we’ve begun to have voices, we have started to display our images, we know the young people are out there, seeking as we did. Our very openness is a way of offering ourselves.

*http://www.oloc.org/projects/

Lee Lynch wrote the classic novels The Swashbuckler and Toothpick House. Her newest book is An American Queer: The Amazon Trail, which is a Lammy finalist. Most recently she was made namesake and first recipient of the Golden Crown Literary Society Lee Lynch Classic Award for her novel The Swashbuckler. She is also a recipient of the James Duggins Mid-Career Award in Writing, and many more honors.Books by Lee Lynch are available at women’s and gay bookstores and at boldstrokesbooks.com