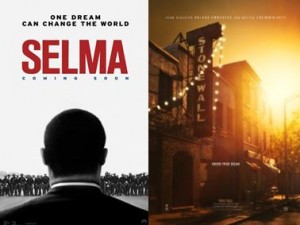

On the 50th anniversary of the historic march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, the Academy and Golden Globe Award winning Eva DuVernay film “Selma” was not without its critics. Criticism ranged from historically inaccuracies to production issues.

On the 50th anniversary of the historic march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, the Academy and Golden Globe Award winning Eva DuVernay film “Selma” was not without its critics. Criticism ranged from historically inaccuracies to production issues.

The film began with scenes from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. receiving his Nobel Peace Prize in Stockholm in 1962 to the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham in 1963 to Dr. King planning the 1965 march in Selma. It was a broad sweep of events that, while connected to the need for social change in Alabama, left some viewers startled.

My late father served in the Alabama National Guard in the 1960s and served the integration of the University of Alabama in 1963 and at the third Selma march in 1965. I have a non-speaking and hardly visible role as a reporter in the film.

Dr. King’s Selma campaign was months in the making. The first march is known as Bloody Sunday due to state sponsored violence to stop marchers. The second attempt is known as Turnaround Tuesday because Dr. King made the decision to turn marchers away from more violence. The third march was successful due to the military presence.

DuVernay compressed considerable history to make Selma and received criticism for doing so. A fuller account of Selma would have been a longer and likely less commercially successful film.

The other repeated criticism was the female treatment of the march and, to a degree, the treatment of Dr. King. I did not have that criticism and, frankly, it did not cross my mind as I filmed my scenes for DuVernay in Atlanta in June 2014. This was a cheap attack on the film and its director.

Still, “Selma” did not receive the attention, critical and commercial, producers expected. Why? One can go sleepless wondering why such things happen. Largely, the competition was great and “American Sniper” was unbeatable at the box office and at the Academy Awards.

2015 also brings moviegoers “Stonewall” forty-six years after that historical civil rights event in Greenwich Village. The actual Stonewall riot was an event that spread over several days. Producers faced the same problem as DuVernay in compressing historic events to fit a conventional film audience.

Further, mainstream media coverage of the Stonewall riots and their significance to our country’s civil rights history was significantly less than for Selma. Media coverage of gays in the 1960s was largely dismissive of gays and written by journalists who largely thought of gays as laughable queens and homosexuals rather than civil rights activists.

I saw a few minutes of “Stonewall” in Manhattan. After 30 minutes, I left for another movie, the superb German “Labyrinth of Lies,” a historical account of a courageous German solicitor who doggedly sought the arrest and conviction of former Nazis protected by the then West German government.

“Stonewall” lost my interest early and I could not see it recovering from such a dismal beginning. I felt I had seen this movie before as I left the theater. I simply did not want to waste my time. I do not know how the film “Stonewall” reaches its climax, but I am familiar with the actual events from documentaries, conversations with elders, LGBT and straight, who claim to have been present at the riots, and numerous books and past articles on the actual event. I do not need a Hollywood version to set me straight on Stonewall.

One gay critic told me the film was fictionalized beyond his belief. Another told me it was “filmed lies.” I also heard it was a straight version of Stonewall. This is a similar criticism leveled against DuVernay as a female director of Selma.

DuVernay consulted elders who attended the Selma march 50 years ago for the film. I hear the same was true of Stonewall producers. If so, the Stonewall elders may be responsible for the tired, clichéd production.

The New York Times said Stonewall choked on its good intentions. Since I also did not want to choke, I departed for the superb historical drama “Labyrinth of Lies.” Set in West Germany in the late 1950s, this film compresses time masterfully in telling its account of a tireless West German attorney who successfully brings Adolf Eichmann to trial for Nazi crimes. It is a brilliant, literate, and engrossing film. It is everything Stonewall should have been.

When it comes to Stonewall, see a documentary on the riots or read a book on the riots, preferably Martin Duberman’s 1994 “Stonewall” or David Carter’s 2010 “Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution.”

In sum, “Stonewall” is not history; it is hodgepodge. The event deserved better film treatment. Perhaps it will get it on the 50th anniversary of the event.

Human Rights Advocate Jim Patterson is a writer, speaker, and lifelong diplomat for dignity for all people. In a remarkable life spanning the civil rights movement to today’s human rights struggles, he stands as a voice for the voiceless. A prolific writer, he documents history’s wrongs and the struggle for dignity to provide a roadmap to a more humane future. Learn more at www.HumanRightsIssues.com