When trans people are imagined in the minds of many folk who’ve never actually met a trans person, we often are imagined as one or two-dimensional male creatures dressed as females that are interested in sex and trans related surgeries. Thoughts of trans people having parents, children, jobs and hobbies seem lost to caricature.

Well, trans people can and often are people of faith. Some are even leaders in their faith communities.

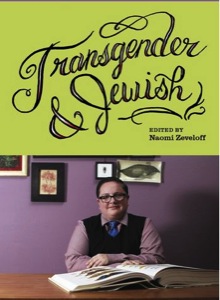

Naomi Zeveloff is the deputy culture editor at the Jewish Daily Forward. Zeveloff had written about gay and lesbian inclusion into the non-orthodox rabbinate for the Forward, and after spending a year reporting on lesbian and gay inclusion, she began wondering about trans inclusion in those same communities. The e-book Transgender and Jewish is the product of that wondering.

What first she found in her basic research was that most of what had been written about being transgender and Jewish had been written mostly for other trans people – written by and to the T-subcommunity of the LGBT community. The essays in this book are intended to speak to a broader audience of people – those outside of an LGBT echo chamber. Transgender and Jewish explores the questions, thoughts, and experiences of non-Orthodox transgender members of the rabbinate.

“Like its transgender members, the Jewish world is always in transition, always becoming, always outgrowing and regrowing rituals (even the ultra-Orthodox aren’t offering animal sacrifices), customs and institutions,” wrote Dr. Joy Ladin, a professor of English at Yeshiva University in the book’s forward. “And though most Jewish communities and institutions are just beginning to recognize the existence of transgender members, as Tevye finds as he tries to fathom his daughters’ marital decisions in Fiddler on the Roof, all Jewish communities and institutions, including the most traditional, struggle with shifting definitions of gender roles and expressions. From this perspective, the birth of a future in which transgender Jews are fully included does not break from Jewish tradition and history but rather grows out of it.”

Jewish tradition is called “living tradition” for a reason – the Jewish faith has a long tradition of changing tradition to fit changing times.

And the living tradition applies to death. Noach Dzmura discussed Jewish burial, and specifically the ritual of tahara, in the essay Does Gender Matter after Death? “The trappings of gender – clothing, hairstyle or makeup – are gone when one is laid naked on the tahara table,” wrote Dzmura. “In many cases, the body doesn’t tell the full story of a person’s gender. For various reasons, many trans people don’t have surgery to make their genitals conform to the norm of their chosen gender. And yet, our tradition tells us that a penis always indicates the presence of a man, and the vagina the presence of a woman. There is no contingency plan for the occasion of a man with a vagina, or for a woman with a penis.”

“What are the communal norms concerning a person’s gender expression,” Dzmura stated later in the essay, “when it differs from the community’s expectations? How do we bury a third gender tumtum – a rabbinic category in the Talmud for a person whose gender is unknowable? How about an androgynous – another rabbinic category for a person who has both male and female genitals? What about someone who wants to honor more than one gender in a long life?”

In rabbinical tradition, asking difficult questions, even as difficult as Dzmura’s, are the norm. Currently, more non-orthodox rabbinical schools have become accepting of transgender rabbis, but that acceptance isn’t fully realized in Jewish congregations. Finding a congregation that will accept trans in the rabbinate is more difficult than finding a rabbinical school that will accept qualified trans students. But the momentum of this living tradition is moving toward the loving embrace of trans rabbis.

Transgender and Jewish spoke to me of how the intersection of transgender and faith not only impacts the individual trans people of faith, but also impacts those in given faith communities who intersect with their trans congregants. And as this book shows, this can be a very positive thing.