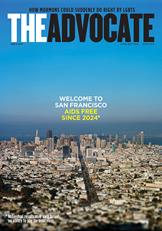

LOS ANGELES — The concept for The Advocate’s April/May 2013 cover story began with a visit to San Francisco General Hospital’s Ward 86, the nation’s oldest HIV/AIDS clinic. In the early ‘80s this was ground zero in America’s battle with AIDS, and the average life expectancy of patients admitted was only 18 months. Now, with numerous breakthroughs in treatment and research toward a cure, writer Jeremy Lybarger asks if San Francisco can become the first AIDS free city.

LOS ANGELES — The concept for The Advocate’s April/May 2013 cover story began with a visit to San Francisco General Hospital’s Ward 86, the nation’s oldest HIV/AIDS clinic. In the early ‘80s this was ground zero in America’s battle with AIDS, and the average life expectancy of patients admitted was only 18 months. Now, with numerous breakthroughs in treatment and research toward a cure, writer Jeremy Lybarger asks if San Francisco can become the first AIDS free city.

Today in Ward 86, the picture is much different. While there is still no cure for AIDS, and the rate of new HIV infections has remained relatively stable, the city is redoubling its assault on the disease that has claimed the lives of more than 19,000 of its residents. Inspired by Hillary Clinton’s 2011 speech at the National Institutes of Health, in which then-Secretary of State Clinton rallied for “an AIDS-free generation,” and emboldened by recent breakthroughs included PrEP and antiretroviral therapy (ART), San Francisco is committed to being the first city to reach zero – zero new HIV transmissions and zero AIDS patients.

Dr. Diane Havlir, the head of Ward 86 and one of the nation’s leading HIV and AIDS researchers, is optimistic about the future. “It’s an exciting time. We’ve all be re-energized by a couple of things. First, by the prospect that with earlier treatment and with PrEP we can dramatically reduce the number of new infections, and secondly, by the fact that a cure – that I can even happen – has been proven.” Citing the case of 14 French HIV patients who started an ART regiment months after infections who have subsequently quit taking the medication with no surge in viral loads, Havlir and her SF General colleagues launched RAPID, a citywide program aimed at getting HIV patients on ART the same day they’re diagnosed.

To that point, Neil Giuliano, CEO of the San Francisco AIDS Foundation, believes the city’s liberal outlook will aid progress. “We still have a ways to go in dealing with shame and stigma,” he says, “but I would venture to say we have gone much further than most other urban, and certainly suburban, communities in this country.”

Looking to go even further, in 2010 the foundation’s board set a goal of cutting the city’s new HIV infections by 50% in five years. “We have an obligation to be aspirational,” Giuliano says. “Do I know that we’re going to hit that goal by 2015? I don’t know what we’re going to do that. One of the things I’ve learned in life is if you don’t set a high enough goal, you’ll certainly never come close to it.”

What could block San Francisco’s journey to becoming AIDS free includes a number of systemic flaws, including a ramshackle economy, income inequality, housing shortages, and unemployment. Michael Scarce, an activist and medical sociologist, argues these factors are the real blockades to the city’s quest for a cure. “If you could choose one city that would be the first to become AIDS-free it could very well be San Francisco,” he says, “and yet all of the comorbidities and socioeconomic factors that intersect with HIV would need to be eliminated if we’re going to truly be AIDS-free. We can provide testing and treatment all we want, but if people at risk aren’t inspired and motivated to have lives worth living we can’t convince them to take advantage of something that might save their lives.”

What the San Francisco AIDS Foundation is hoping will help is the centerpiece of their 2014 plan: a new, $10 million gay men’s health and wellness center. The facility, located on Castro St, will consolidate three separate agencies: Magnet, a sexual health clinic; the Stonewall Counseling Center; and the STOP AIDS prevention office. This new facility could be moving San Francisco toward Dr. Havlir’s goal of a city in which diagnosis, treatment on demand, and outreach services such as housing, substance abuse counseling, and mental health counseling are integrated under one umbrella of care.

Read The Advocate’s full April/May 2014 cover story now at: