Kevin Beiser grew up in a family whose challenges included constant moving, homelessness, school suspensions, low expectations from teachers and addiction. Nevertheless, he is now president of one of the largest school districts in the nation, San Diego Unified.

“I remember my first couple of days at middle school,” Beiser recalls. “I was following my two older brothers, who were I guess real troublemakers and not the best students.”

In fact, on one occasion, in fifth grade, Beiser says one of his brothers was suspended for punching his teacher.

“They thought I would be just like my two older brothers,” says Beiser. “The teachers were kind of shocked when they realized I was getting good grades, and was quieter and ended up on the debate team in high school.”

Yet today Beiser is proud of his brothers for working hard to overcome their challenges. In fact the educator practically beams with pride when he notes that, while his brothers didn’t graduate from high school, they ultimately earned GEDs and are in college today.

“My dad said, right before he passed away two Christmases ago, that he was very proud of me,” says Beiser. “It felt really good, because it’s been a rough go for my mom and dad. One of the reasons I worked so hard to go to college was that we grew up in pretty deep, deep poverty.”

There was a time when the Beiser family lived in a homeless shelter, and another time when they lived in a tent.

“For the first part of my childhood, I was the youngest, and I couldn’t play in my older brothers’ reindeer games,” Beiser recalls. “First we were a family of all boys, then my mom remarried and had two more kids. Now I was not youngest; and now there was a girl in the family, Danielle.”

What was different about Kevin Beiser from his brothers that allowed him to succeed in school where the family’s struggles seemed to hold his siblings back? The answer to that question is also a glimpse into what led to his love of education – a love so strong that it has made him a trailblazing school board member, vice president and now president who is shaking things up at SDUSD.

Key to his trajectory, says Beiser, was the influence, encouragement and belief in him of a handful of teachers, his mom and counselors in middle and high schools – despite the fact that on paper, he should have been seen as “at-risk” of being a lost cause.

“I had one counselor who told me I absolutely could go to college,” Beiser says. “And that I should.”

Meanwhile, at home, the electricity was sometimes turned off because the bill was unpaid.

“And back in the 1980s, they could turn off your water too,” Beiser recalls. “That happened. One time we lived in a tent in my grandma’s backyard. We’d have to make do. It was really rough.”

But, says Beiser, all of those problems made school seem all the more attractive.

“People say, ‘oh my God,’ Kevin; you’ve overcome so many problems. But everybody has adversity in his or her life. I know people who grew up in middle class families, but they had very different challenges. Dad was always working and they never had the opportunity to spend time with him.”

However, Beiser is human and can’t help but poke a little fun at himself for comparing homelessness and abject poverty with insufficient quality time with dad.

“I mean, cry me a river,” he says, chuckling. “You have electricity, water, food and clothes and you don’t have to put cardboard in the bottom of your shoes because your feet get wet when it’s raining because it’s a rainforest outside.”

And rain it did. Beiser grew up in a Portland suburb called Gresham.

“They have great schools in Gresham,” Beiser says – true to form, always bringing conversations back to education.

Yet Beiser only got his start as an educator after a meteoric rise in his first career in big-box retail management. He once found himself the youngest person in a meeting of fellow top company executives at Wal-Mart headquarters in Bentonville, Ark.

“I’m pretty sure I was the only gay one there too,” he says with just a hint of sarcasm in his voice.

Beiser earned his B.A. degree from Willammette University in Salem, Ore., later earning a master’s in education from the University of Phoenix in San Diego. Beiser has two teaching credentials, one in social science and another in mathematics. He is a former Weeblo, Cub Scout, Boy Scout and Little League outfielder.

“I loved football when I was a kid,” Beiser recalls. “And I was in marching band in high school, where I played percussion since fifth grade. You know, chimes, xylophones, drums and cymbals.”

Beiser says he knew there was something different about him when he yelled “change it back!” after someone changed the channel away from a trailer for Risky Business featuring the iconic scene of Tom Cruise lip-syncing to “That Old Time Rock-N-Roll.”

“One of my brother’s said, ‘Why Kevin?’ and dad said, ‘Yeah, why, Kevin?’ Of course, my mom saved me by saying I liked the song.”

It would be years before Beiser would officially come out of the closet.

“Back while I was growing up in the late seventies and eighties, there were no images of gay men raising children together,” he says. “There was no Will & Grace. All there were were images of how horrible people looked in the ‘gay parades.’ The media would only show the most egregious costumes and sexually overt, outlandish getups – which, watching that with your parents back in the day was, well, kind of scary.”

Things have improved significantly for LGBT youth since then, according to Beiser.

“Things are better today,” he says. “You grow up thinking you are the only person in the universe who feels that way. But once you figure out there are other people who are just like you, then you realize it’s OK – that there’s nothing wrong with you just as you are.”

Ironically, Beiser came out while unknowingly working at a gay restaurant.

“I was 20 years old and working as a waiter at Hamburger Mary’s in Portland, Ore.,” says Beiser, who retains much of his Boy Scout charm and apparent naiveté to this day. That was no doubt in evidence during his first few days as a basically closeted gay youth unwittingly working in a trendy gay eatery.

“I was home for summer break and working as a waiter,” he said. “I knew being a waiter was a good job, because my mom was a waiter at Denny’s and I had worked at the Pizza Hut before leaving for college.”

But Hamburger Mary’s was no Pizza Hut.

“I noticed there were a lot of people there who seemed kind of … different,” says Beiser without a shred of irony. “Once while I was on a break, I could hear this other waiter talking to this lesbian cook about this gay bar that he went to the night before and how he met this guy. I think they could see that I was listening intently and that I didn’t really know what was going on in my life. So, he invited me to go out with him to the gay bars around Portland one night. It was very liberating and it was a great time to be young and gay in Portland.”

From that point on, Kevin Beiser stopped hiding who he was. Although at 17 he had had an ongoing relationship with another male youth, he considers the Hamburger Mary’s experience to be his “coming out” moment.

Although Beiser does not shy away from standing up for LGBT equality in his role as SDUSD president (as he proved again during a recent press conference, where he strongly reaffirmed the district’s support of California’s transgender-students-rights law, AB 1266, which is currently under attack by radical-conservative forces), he is first and foremost focused on the cause of improving public education in California for all students.

“I want to thank San Diego Unified trustee Richard Barrera for joining me in getting front of this issue,” he says. “This law is modeled after the policy that has been in place without incident for 10 years at L.A. Unified. And here at San Diego Unified we have been dealing with the issue of transgender students on a case-by-case basis in the same way without incident for many years.”

As much as Beiser laments the politicization of AB 1266, he also regrets the long, downward march of spending on public education in the Golden State.

“California was known around the United States and around the world for having one of the best public education systems anywhere,” he said. “That’s in large part because California spent more money on public schools per pupil than anywhere else. That allows you to have more programs, more music, more teachers, smaller classrooms, more diversification – better education.”

Among the most unfortunate losses that have come as a result of diminished funding of California’ public education system during the past four decades, says Beiser, are the elimination of busses for field trips, which make school exciting, enriching and fun for students; as well as the loss of music classes, extracurricular programs and athletics programs.

“Instead of getting plugged into gangs, kids could get involved in an athletic team, or in a club,” he says. “But you need money to pay for the adults to administer these things. And that’s what it used to be like for public education in California. What it’s like today is far different and not as good for kids or for society.”

In fact, Beiser points out, since the decades of dropping dollars for education, the state has fallen down the ranks to 49th in the U.S. in per-pupil spending by many measurements.

“That’s why we struggle to keep up in test scores, and why California’s public education system does not live up to the promise of the (19-) ‘60s and ‘70s,” he says. “That’s why we’ve gone away from the state constitutional promise of a good education for every Californian who wants to do the work to get that good education, including K-12 and including college.”

However, Beiser demurred when asked about the often-cited correlation between the decline of public education in California and the passage in 1978 of Proposition 13, which decreased existing revenues and limited future property taxes. Property taxes are the main revenue source upon which public school funding is based. To some extent, Proposition 13 tied property taxes to the value of properties as they were in 1975.

“I can’t speak to Proposition 13; I don’t know a lot about that,” he said. “What I would say is don’t tell me what your priorities are; show me your budget and I’ll tell you what your priorities are. We rank toward the bottom in California on what we spend per child and we rank poorly in student performance. Massachusetts spends near the top and they perform near the top. It’s not rocket science.”

Beiser says the past five years have been a series of draconian budget cuts for public schools in California.

“There are some areas where I have fought very hard on the school board to make sure we have three votes not to cut music and the performing arts,” Beiser says. “The research is definite. Not only does music, for instance, help with math, but students who get involved with music, arts, choir, visual arts, performing arts, etc., do better in all of their other courses.”

Beiser commends the creativity of teachers for developing so-called “integrated art” curricula into other class subjects in the face of cuts to direct funding of art in schools.

Says Beiser, it is important for members of the public to remember that the five-member school board is not the same as district administration. In fact, he says a fair analogy to the structure of large districts such as San Diego Unified is to compare the school board and its president, which collaborates with the district’s school superintendent and her staff to the way a corporation’s board of directors and chair work with its CEO and her staff.

While SDUSD’s “CEO,” Superintendent Cindy Marten, oversees the sprawling district’s day-to-day operations, Beiser and his fellow board members advise and consent (or oppose) on policy matters. One area where the board does have pre-eminence over the administration is with the district’s $2.5 billion budget. Although the superintendent presents a fully fleshed out budget proposal each year, the school board can make modifications and must approve final funding.

“When I first got onto the school board, the superintendent wanted to cut 50 percent from music and another 50 percent from school police,” Beiser says. “We pushed back.”

Ultimately, says Beiser, other cuts were found.

“I pushed back all the way,” he said. “We cut nothing from music or police.”

Beiser says he won’t know whether or not sticking to his guns on music and school police was popular with voters until June and November, when he stands for re-election.

The school board president’s “day job” is as a math teacher in the Sweetwater Union High School District. It was in that capacity that he built his reputation as a passionate educator and reformer.

“My obligation is to do the best job I can to improve schools,” Beiser responds when asked if he feels any special obligations to represent the LGBT community well as the first openly gay man to be elected to SDUSD.

“I mean, that’s why I ran. I didn’t do it because I’m gay; I didn’t do it to carry the banner for gay kids in schools – although that’s an added bonus. I did it because for several years, I was part of a team that turned around a school in South Bay.”

Beiser says when he started working at Granger Junior High it was the lowest performing school in San Diego’s South Bay region.

“It was in ‘Program Improvement,’” he recalls. “Parents were pulling their kids out of the school and sending them somewhere else because it had such a bad reputation.”

So bad was the reputation at Granger that the word on the street was “Granger is Ghetto,” says Beiser.

But eventually, after overcoming a spirited but brief internal-politics battle at the school, and leading an effort to making after-school tutoring for students with Ds and Fs mandatory, along with a heavy dose of moral support and encouragement for students – not to mention the creation of multiple clubs and extracurricular programs – Granger won national recognition as a School to Watch

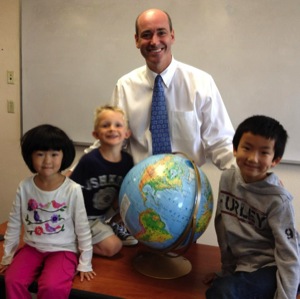

“A common problem plaguing low-income schools is poor attendance; part of the way to change that and what we did at Granger is creating attendance incentives and perfect attendance awards, lots of motivation to get kids to show up,” says Beiser, who lives in San Diego with his husband Dan Mock and their three dachshunds. “It’s not about enforcement; it’s not about the stick; it’s about the carrot.”

As Beiser puts it, the promise of public education is breaking the cycle of poverty.

“That was me when I was a little kid,” he says. “Someone told me, ‘you’re going to go to college. That was my mom and a teacher. I tell my students, you’re going to go to college. But you can’t get there if you’re not in class and your butt’s not in that seat.”

Beiser also takes his seat-at-the-table approach to community issues, such as the closure of the San Onofre nuclear power-generating station because, he says, environmental issues matter to public education.

Some experts say it was SDUSD’s chiming in publicly with concerns about students and families’ health and safety, which may have been the straw that broke the camel’s back and led to the final decision to close the troubled facility.

“We have also received a lot of national recognition as a district for our green initiatives,” he said. “By going solar on a significant scale in our facilities, we have lowered the amount of money we spend on energy, which frees up resources for education.”

Asked if a run for higher office might be in the offing sometime in the future, Beiser returns to his singular focus – education.

“I’m all about the work I’m doing now; I want to continue to improve education at San Diego Unified.”

While it’s true that California ranks near the bottom in per pupil spending, it’s also true that it ranks near the top in teachers salaries — fifth highest in the nation according to the Sacramento Bee.

It’s also true that — by law — California must spend almost half of the state budget on public schools.

How interesting that Beiser doesn’t talk about any of that.

There is plenty of money for education in California, but it’s mostly going to teachers (average salary almost $70,000 for nine months of work), not students.

Kevin Beiser seems like a nice guy, but like other liberals he is fronting for the teachers unions who are more interested in their pay and benefits than they are in the welfare of the kids they teach.

The liberal answer is always “raise taxes,” but that answer doesn’t make sense in a state like California that already has some of the highest taxes in America.

The wealthy people who pay most of those taxes (the top 1% of income earners pay 50% of all state income taxes collected according to the State Franchise Tax Board) aren’t going to put up with it forever.

They’ll just up and move somewhere else. They don’t have to stay here.

Why should I, as a gay taxpayer, go along with the greed of teachers who have much better pay and benefits than most gay folks have?

Sorry, don’t think so.