The struggle for LGBT equality is part of the fight for civil rights for all minorities, and a continuation of the Civil Rights Movement started by Dr. Martin Luther King, Bayard Rustin and other legendary activists during the 1950s and ’60s, according to leading LGBT-rights activists.

Yet, says author and activist, Rob Smith, who is an Iraq War veteran, many in the African American community resent conflation of the Civil Rights and LGBT-equality movements.

Smith, who served in the United States Army as an infantry soldier during the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell epoch, has been the object of a triad of biases, including discrimination as a black man; prejudice because he is a gay man; and bigotry because he is a gay African American.

Ironically, the fact that Smith is gay and black has engendered discrimination not only from within the African American community, but also via separation in his own gay community.

“The only way that I am really going to be treated as gay walking down the street is if I’m literally walking hand-in-hand with the guy I am dating or wearing a bright, rainbow T-shirt or something like that,” says Smith. “But I am treated as a black man from the second I leave my door every single day.”

Smith says it is up to him to integrate both identities.

“So, it’s always going to be the same act that plays out first in my mind,” he says. “And it’s always going to be something that affects society’s treatment of me … I have to reconcile both of those things.”

While there are those who resent conflation of the Civil Rights and LGBT-equality movements, Smith believes support from African Americans can help desegregate the two civil rights struggles.

“It is important that we have black Americans and people of color out here [who] are advocating for LGBT rights because we can’t continue to put forth this image that being black and being gay are two separate things,” he says. “That being gay is just a white thing.”

Smith demonstrated his commitment to what he calls “the civil rights issue of our time” in no uncertain terms when he chained himself to the White House fence in 2010 to protest Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell. But when organizers first called him to participate in that protest, Smith had reservations.

“As somebody who is a black male, I think a lot about staying out of jail,” Smith told LGBT Weekly.“I think a lot about not becoming a statistic in that way.”

But he also thinks a lot about how his forebears who led the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and ’60s went to any length to create change by way of civil disobedience, protests, sit-ins and other nonviolent means of standing up for equality.

“I didn’t know if there would be a black face there if I didn’t show up,” Smith says. “So I did.”

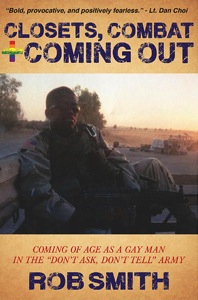

Smith’s battle with his “dual identity” as a black, gay man is detailed in his book, Closets, Combat, and Coming Out: Coming of Age as a Gay Man in the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell Army. The book, he says, is the first published Iraq War memoir written by an African American soldier and the first memoir by a gay Iraq War veteran, black or otherwise, in the post-DADT era.

“One of the reasons why I wanted to do this book and I wanted to restart this conversation is I feel like we’re kind of leaving our LGBT veterans behind and there is a lot of work that needs to be done. There is still no nondiscrimination policy in regards to sexual orientation in the military right now.”

Smith is under no delusions that a book, which, in part, spells out the need for greater support of LGBT equality, will be a unanimous hit among African Americans.

“Just the fact that (March on Washington chief organizer, Bayard Rustin) was openly gay is something that is erased when he is spoken of in mainstream African American circles is unfortunate” says Smith.

Rustin was a Quaker. However, it was another Quaker who inspired the woman who is now helping to lead a national campaign to win approval for a Bayard Rustin U.S. postage stamp.

That woman is Mandy Carter. She was the main honoree and keynote speaker at the first annual Bayard Rustin Honors ceremony last year. Her life changed course from that of a Schenectady, New York teenager to that of a civil rights activist during one 40-minute social studies class in high school.

“I was a junior in high school in 1965,” Carter told LGBT Weekly during a recent phone interview from her home in North Carolina.

“In upstate New York we were just beginning to hear about what was happening down south. Our social studies teacher, John Hickey – I’ll never forget his name – invited some young white guy from this group called the American Friends Service Committee.”

The young man was a Quaker – a member of the pacifist faith tradition, called the American Friends Society and its service committee. Quakers helped lead the abolitionist movement in the nineteenth century; and in the 1950s and ’60s, were at the cutting edge of nonviolent resistance that was so revered by Dr. Martin Luther King.

Carter went to an AFSC training camp where she learned about peaceful, nonviolent civil resistance. There, she also learned about the “power of one” as the Quakers call individual action for change.

“What I learned was that each and every individual has the power to impact change,” she says.

Forty years later, a partial résumé of Carter’s activism includes leadership roles ranging from grassroots activist to co-founder and executive director at organizations such as the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s Poor People’s campaign, Joan Baez’s War Resister’s League, Southerners On New Ground (SONG), the National Gay & Lesbian Task Force, the National Black Justice Coalition and the Creating Change Conference.

The 26th annual Creating Change Conference, which seeks to advance freedom, equality and justice for LGBT people, was held in Houston earlier this month.

“It was the biggest to date,” Carter says. “We had about four-thousand people in Houston, and it was quite an event.”

Among those 4,000 lesbian, gay, bi, transgender and allied conference-goers were people of all races, ethnicities and socio-economic statuses.

“When people in the Civil Rights Movement – capital ‘C,’ capital ‘R’ – think of ‘gay’ as meaning only gay, white males, they’re pointing at the movement and saying, quite mistakenly, that there are no black LGB or T people out there marching here with us for racial equality.”

Carter’s place as a highly accomplished, lesbian, African American leader of both the Civil Rights and the LGBT-equality movements is an inconvenient truth for any who would refute or deny the inclusion of LGBTs in the former movement.

“But they are one,” Carter says. “I don’t like the idea that the fight for LGBT equality is ‘the civil rights movement of our time.’ It’s a continuation of the fight for justice and equality for all that was fought for by Dr. King and Bayard Rustin.”

In San Diego, legendary NAACP activist, educator and former 79th Assembly District candidate, Dr. Patricia Washington sees a mixed bag regarding the state of LGBT equality and the struggle for equality in the African American community.

“While we are well on our way in terms of celebrating people like Harvey Milk, Bayard Rustin and others, we have a long way to go in terms of recognition and appreciation for all they’ve done for us,” she says.

In fact, Rustin himself said that LGBT Americans might be the best indicator for gauging America’s progress toward achieving its promise of freedom and justice for all.

“The question of social change should be framed with the most vulnerable group in mind: gay people,” said Rustin in a 1986 speech delivered to the Philadelphia chapter of Black and White Men Together.

According to Rustin, “Blacks are no longer the litmus paper or the barometer of social change.”

Rustin’s message reverberates through activists, such as Smith, Carter and Washington, exhorting America to ask, “What about LGBT people; are we free yet?”

‘Closets, Combat and Coming Out’

In Closets, Combat and Coming Out, the first gay Iraq war memoir published post-DADT repeal – and the first Iraq war memoir written by an African American, period – author and activist Rob Smith comes to terms with his sexuality against the backdrop of the hyper-masculine and hyper-homophobic U.S. Army.

After surviving the notoriously brutal Infantry Basic Training as a chubby, fresh-off-the bus, 17-year-old, Smith is equally tortured by his homosexuality, privately battling isolation, paranoia and suicide, while remaining closeted to all but a few of his colleagues. At his first duty station, he finds himself in dangerous territory – on both military and personal fronts – after the United States declares war on Iraq and his unit is one of the first called in, after the initial invasion.

Honest, frank and eloquent, Smith reveals not only his personal experiences as a gay military man serving under DADT, but reminds us that for many LGBT men and women, the battle for equality in the eyes of the military is not over – regardless of the repeal of DADT transgender soldiers are still barred from serving openly, the U.S. military still does not have a nondiscrimination policy in regards to sexual orientation and thousands who were dishonorably discharged under DADT remain stripped of the hard-earned benefits to which they were rightfully entitled.

Closets, Combat and Coming Out: Coming of Age as a Gay Man in the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell Army by Rob Smith

© 2014 Blue Beacon Books by Regal Crest

ISBN: 978-1-61929-132-4

Available at amazon.com and