In 1942, their countrymen betrayed those who pledged it. Can a musical tell their story and prevent that from happening again?

An interview begins with the interviewer mispronouncing a genuine Hollywood legend’s name.

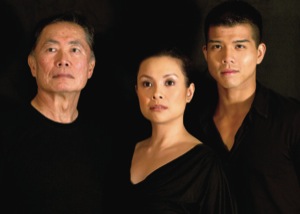

“It’s Tuh-kay,” said George Takei, most famous for his role as Lt. Sulu in the original, groundbreaking NBC television series, Star Trek, and several big-budget sci-fi feature films of the Star Trek franchise. “Tuh-kī would mean ‘expensive.’”

Takei adds, “Now that doesn’t mean (because it’s not pronounced “Tuh-kī”) that I’m cheap.”

“Takei means ‘warrior’s well,’” Takei explains, saying that his surname might indicate that he comes from a line of bartenders to the samurai class.

“I’ve been running lines with Brad all morning,” Takei says over the phone. “But this is perfect. I’m ready for a break; let’s do the interview now.”

In addition to being his rehearsal partner one recent morning, Brad Takei is George Takei’s husband. The couple married during that fleeting period of marriage equality in California before the passage of Proposition 8.

As a very young child living in Los Angeles in the weeks immediately following the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor during the holiday season of 1941, Takei experienced the terrifying events portrayed in his new musical, Allegiance, playing Sept. 7 – Oct. 21.

At first, it might seem hard to imagine why the story of the internment of a Japanese-American family would make for a good musical. But, at second thought, what better way to communicate the writhing emotions embroiled in the experience of betrayal by ones’ own countrymen than through song; through music; and yes, even through dance?

The warrior’s well of memories that is one family’s legacy – that of the real-life Takeis’ as shared with San Diego LGBT Weekly by its most famous member helps fuel the on-stage story of the Kimuras. Lending George Takei a hand in portraying his character, “Sam,” in his earlier life when he was more apt to be called “Sammy” is Glee’s Telly Leung.

“Telly and (director) Stafford Arima, and (writers) Lorenzo Thione and Marc Acito, Kuo and Lorenzo Thione, as well as lyricist, Jay Kuo are amazingly talented artists,” says Takei about why he thinks Allegiance is a musical that could become a phenomenon. “And The Old Globe has a history of, and is great at producing hits, both commercially and critically.”

“Then too,” says Takei. “… this is my legacy project.”

That legacy began when George Takei’s tiny five-year-old’s hands, which would one day grow into the steady helmsman’s hands of the USS Enterprise, were no match against the bayonet-brandishing U.S. soldiers who invaded his family’s Wilshire District home in 1942.

“My remembrance is that of an innocent child from five to eight,” says Takei. “Of course when the soldiers came, it was a terrifying morning. My brother was four; my baby sister was a year old.”

The involuntary internment of American citizens who thought they were Americans without any asterisks, but who, because they were simply of Japanese descent remains one of the darkest blots upon the conscience of the American psyche. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, filled so-called “War Relocation Camps,” with more than 110,000 innocent Americans.

“I grew up in L.A.,” Takei said. “I was as American as anyone else. Yet I and my entire family were picked up and taken to what they called an ‘assembly center’ at Santa Anita (horse-racing track in Pasadena).”

From Santa Anita, where the Takeis lived in a horse stable for a while, the U.S. government sent the family to a camp in Arkansas called “Rohwer.”

Because he was so young and, as Takei puts it, seeing things through the eyes of wonder that only children know, fear was soon replaced by excitement.

“You have to remember, we were from Los Angeles; I was born in East L.A. We moved, of course, and grew up near … the famous Bullocks Wilshire department store. I had never seen snow. When we got to Rohwer, the entire place was white with snow. I had never seen such a sight. It was – well; it was beautiful!”

Then, when summer came, there were the creeks.

“And we caught frogs and there were polliwogs.”

By the time Takei and his parents and siblings were freed, Takei was eight.

“It must have been so hard for my mom and my dad,” he recalls. “We didn’t go right back to the Wilshire District. You see, they took everything away from you. We had nothing. At first, we lived in the Skid Row area of Los Angeles.”

Takei says those first days back in L.A. were unbearable.

“The stench of urine was everywhere. There were people; scary, ugly people, falling on you as you walked down the street. My baby sister said to my mother, referring to the camp, ‘Mama, let’s go home.’”

The Takeis were of the Nisei generation, a Japanese term meaning second generation members of an immigrant family, the first to be born on the soil of their new country. Their children, including George, were Sansei, or third-generation Americans. Yet, despite their mistreatment by their own government, both Nisei and Sansei Takeis still believed in the America promised in history books and the documents of its founding. By the time George Takei was a teenager, he began engaging his father in deep discussions on the topic of equality and civil rights. Takei’s father was an engaging and philosophical conversationalist. But there was one talk he regrets.

…

Continued from San Diego LGBT Weekly newsmagazine …

“Daddy,” Takei recounts. “You led us like lambs to the slaughter.”

“I regret saying that. I realize I hurt him. I wanted to apologize, but he said, ‘maybe you’re right.’ I will forever carry that with me. He closed the door and I thought I would apologize the next day; but that never happened.”

As the Takeis lives in Los Angeles began to return to a semblance of normalcy, George landed a part in Fly Blackbird Fly, a play about college students demonstrating.

“It played at the Metro Theatre on Washington Boulevard,” Takei said. “Then it went to New York, off-Broadway at the Billy Rhoades Theater.”

He studied drama at UCLA. Acting work came quickly for the hardworking, driven and focused Takei. One role led to another, including a big break when he played a Chinese cannery worker opposite Richard Burton, who also played a cannery worker, in Ice Palace.

“Richard Burton’s character worked his way up through the cannery business and ends up opening his own cannery,” Takei explained. “He hires my character, Wang. I become his majordomo, which is like a butler.”

In that role, Takei, a newcomer in his first important role in a big-budget Hollywood film found himself working directly with the legendary Welsh actor throughout the production.

“We aged through the story,” Takei said. “Makeup for old age back then was painful, very painful.”

Ice Palace presented Takei with a rare opportunity, one he knew that many actors with many more years of paying their dues would have done almost anything to have. Takei felt fortunate and took the opportunity to prove his dedication and talent.

“Warner Bros liked me,” he recalls. “I got parts on Hawaiian Eye” (a private investigator ABC television series, which aired 1959-63).

“I was the envy of all my classmates,” he said. “But UCLA was very supportive; my professors were very indulgent; and I did go on to get my bachelor’s and masters degrees from the Theater Department.”

And the rest is history and history continuing to be made by Takei as his career continues to take unexpected and adventurous turns.

The title for the new musical playing this month at The Old Globe was inspired by something that had been at the root of Japanese American internment – something that was suspect.

“Allegiance,” Takei explained. “Our allegiance to our country was suspected; it was a summary roundup on the West Coast. It was the most irrational thing, because there were lots of Japanese Americans in Hawaii, the place where the attack on Pearl Harbor actually occurred, but they were not sent to camps.”

Takei went on to explain an epidemic of “West Coast war hysteria” that made the entire Pacific coast ripe for scapegoating.

“There were no charges, no trials,” Takei said. “We have a system called due process that was completely ignored. They even raided orphanages!”

But, according to Takei, there was something else happening that was even more sinister than the war fever that led to American citizens, who just happened too be of Japanese descent, being imprisoned, including women, the elderly, children and infants, without ever being charged with a crime or being given the due process guaranteed them as U.S. citizens by the United States Constitution.

“A lot of farmers wanted the land Japanese immigrants owned. Immigrants couldn’t actually buy land, so you see, but people like my grandfather were smart and bought and developed the land in their children’s or grandchildren’s name”

Takei’s grandfather developed land in the Sacramento Delta, and area then called Florin.

“Some of the (non-Japanese American) farmers used the paranoia to take our property and our land,” Takei said. “You know, they would say, ‘those inscrutable Japanese.’ The destruction of the Japanese American community is our singular point during World War II. Yet, Japanese Americans rushed to enlist after Pearl Harbor.”

But when they went to recruitment offices, they found something less than marching orders awaited them.

“We were labeled ‘enemy non-aliens;’ citizen in the negative,” he said. “Suddenly they rounded us up. But after some time, as they realized they need as many soldiers as they could get, they opened up military service to Japanese Americans.”

But any would be Johnny-get-your-gun with Japanese ancestry first had to prove his loyalty.

“There were loyalty tests.” Takei said. “Question 27 asked everyone over the age of 17, male or female regardless of age, “are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty, wherever ordered?”

Meanwhile, the more insidious Question 28 created anxiety in the interned Japanese American community. It read (but was later revised for Issei), “Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any and all attacks by foreign and domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese Emperor, or any other foreign government, power, or organization?

For Issei (immigrants), saying ‘yes’ to question 28 would mean they would not have a country to call their own. Meanwhile, their native-born American children, Nisei were fearful of answering “yes” to Question 28 because that could be construed to mean they had previously held loyalty to the emperor of Japan.

“But what was the worst thing to happen was for those young men who said when asked if they would serve the United States in the war: ‘I’m an American. I will serve, but not as an internee. I will go to my hometown draft board. They were rewarded with being taken from the camps to prison.”

Takei believes the strength and weakness of our democracy is that it’s a people’s government.

“That’s why the story of ‘Allegiance’ is important to me and I think it will also be to the American public,” he said. “The story takes place sixty years after the internment, which happens to be 2001. I see what has happened to Arab Americans, Muslims in our country – even Sikhs, who have been murdered because someone thought they were Muslim.”

Takei recalls the story of an Arab American chemist working in a university laboratory who was whisked away by the FBI shortly after 9/11.

“He said, ‘I’m an American; I’m an American,'” Takei said. “His wife was frantic and his family were terrified, but he wasn’t given due process before he was apprehended. We know that what happened to us World War II can happen today, because it has happened in the last few years to certain groups.”

Eventually, says Takei, the chemist was released. The government filed no charges.

Takei also sees a corollary message in ‘Allegicance’ for LGBT Americans and our community’s struggle for basic civil rights.

“I’ve been doing a lot of talks on that topic,” he said. “May is Asian American heritage month; June is Pride month. I’ve been tying the internment to the inequality of the LGBT community. We were confined by real barbed wire back then. Now we as LGBT people are slowly cutting down these legal barbed wire fences that are the irrational depravation of equality from people just because they are different. All these legalistic barbed wire fences have to go. Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell is gone, but marriage equality remains a challenge.”

What g. Takei said to father that he regrets not on website

Please check again!

Website search for Takei only lists this article. Is it possible for you to share a link?

You were right. Sorry for the confusion. Thanks for visiting LGBT Weekly; and thanks for helping us keep our content as good as our readers deserve. Here’s the link. (-Ed.)