Many, if not most leaders in the American labor movement started life with humble beginnings; and it was often their upbringings that motivated and propelled them to fight for the rights of the working man, woman and child. Along the way, labor’s best and brightest found themselves flanked by equally fine leaders from the LGBT-equality movement.

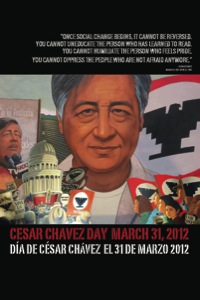

The early hardships faced by legendary civil rights activist César Chávez were clearly prime motivators for his barrier-breaking work. Chávez’ legacy is one of an iconic labor leader who was essential to the creation of the California farm workers’ movement and the founding of the United Farm Workers (UFW). Chávez was the UFW’s first president, but he was always the first to say that it was not his efforts as much as it was the work of tens of thousands of regular labor activists who have made real the most important gains to which the labor movement may legitimately lay claim.

At the same time, Chávez was the first major civil rights leader to support gay and lesbian issues visibly and explicitly. He spoke out on behalf of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people in the 1970s. And in 1987, he was an important leader of the Second National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights.

“César Chávez did not only speak at our 1987 March on Washington but walked the entire march route. His granddaughter Christine Chávez told me that it was the biggest crowd he ever spoke to,” said former National Gay and Lesbian Task Force board member and San Diego city commissioner, Nicole Murray Ramirez. “He never forgot the support the UFW received from the gay community.”

Murray Ramirez came out in support of the unions again in 2009 when he joined other LGBT activists in siding with Unite Here Local 30’s boycott of Old Town San Diego Historic Park’s restaurants, Fiesta de Reyes and Barra Barra. Unite Here Local 30, which had worked with marriage-equality organizations on the Manchester Hyatt boycott, were boycotting the restaurants because the owners had planned to lay off all past employees and reopen the establishments as non-union workplaces.

Murray Ramirez said at the time, “I am not only a gay man, I’m Latino; and consequently the treatment by Chuck Ross of his long time Latino employees and the firing of them, because he’s anti-union, is very upsetting to me and it should be to the GLBT community.”

Also involved in the 2009 support of Unite Here was Lorena Gonzalez, secretary-treasurer and CEO for the San Diego and Imperial Counties Labor Council, AFL-CIO. Said Gonzalez, “I’m the daughter of a nurse and a farm worker, so I grew up in the labor movement. I’ve been heading up the Labor Council for five years continuing their work to give every single worker a voice and a fair shot to build their own place in the world.”

Harvey Milk, the first openly gay man to be elected to public office in California was an early supporter of the California grape boycott organized by the UFW and led by Chávez. Milk understood the benefit of building coalitions with the labor movement early in his political career. A Teamster organizer asked for Milk’s assistance with gay bars during the Coor’s Beer boycott in the ‘70s. In return Milk asked the union to hire more gay drivers. Following this joint action the market share of Coors in California dropped from 40 percent to 14 percent. The boycott was successful.

Again in 1978, the LGBT rights and labor movements came together. A coalition of LGBT and union activists jointly defeated the Briggs amendment, which would have not allowed LGBT teachers in California’s public schools.

While the high-profile successes of the labor movement have been well documented and well recognized through the decades, much of the gains in terms of acceptable workplace practices that are now considered standard came about because of the (ongoing) efforts in pursuit of workers’ rights via alliances such as that of the LGBT–rights and the labor movements, say experts from both camps.

As Gonzalez put it, “People often only know about labor issues like collective bargaining and prevailing wage, but so many other things we take for granted now have come from the labor movement. Sick leave, weekends, equal opportunity employment, workplace safety, and the 40-hour workweek are all products of the labor movement.” She credits members of the LGBT community, such as Murray Ramirez and Milk for their contributions to those ends.

Chávez’ United Farm Workers union inarguably played a role in helping guide presidential cabinet members along their paths to powerful posts in the federal government. U.S. Labor Secretary Hilda Solis, a former California state legislator and congresswoman, was quoted in the Los Angeles Times this week as saying, “Coming up the ranks in California, I had the privilege of working alongside many UFW leaders. No challenge was too great. No corporation or politician was too powerful. They built a union unlike any that had come before it. They turned a community into a movement – and that movement became a powerful force for change.”

However, just as the struggle for LGBT and other minorities’ civil rights is an ongoing, unfinished process, so too remain unaccomplished goals for the labor movement.

“We need to do a better job explaining that we’re working for all workers, union and non-union,” Gonzalez told San Diego LGBT Weekly. “Our goal is an opportunity for everyone to earn a living, everyone to be treated with respect, everyone to have the chance to be heard. I certainly think a union is the best way to accomplish those goals, but the most important thing is that we all get there together.”

Likewise, according to her, the efforts of the labor movement are intertwined with the goals of the LGBT community. Said Gonzalez, “We’ve always said that work unites us all. Members of the LGBT community may often face additional challenges, but they also need the same protections in the workplace that everyone else deserves.”

The relationship between the LGBT movement and the labor movement has been one of mutual assistance to achieve common goals.

“Going back to Harvey Milk working with the Teamsters to boycott Coors, LGBT and labor have worked together for decades,” said Gonzalez. “We ran phone banks against Prop. 8; and I am a staunch advocate for marriage equality. I have always been committed to the LGBT community as an invaluable ally and can’t imagine one without the other at this point.”

She points to the aforementioned common goals as the reason she can’t imagine the two movements ever parting ways.

“At their core, both movements are about basic dignity,” she said. “Will we be treated fairly at work? Will we have the opportunity to live our own lives? Whether it’s social issues or economic issues, we’re all just talking about what’s fair and decent.”